First impressions, we are told, are lasting.

First Impressions, we are also told, is the title of Jane Austen’s ur-version1 of her novel Pride and Prejudice, a fact that I might not know but for the fact that a perhaps ill-advised 1959 Broadway musical thereof titled itself First Impressions, and ill-advised Broadway musicals are one of my passions.

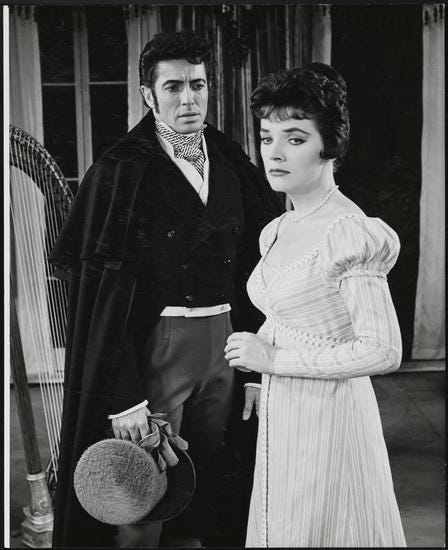

Not much else need detain us about First Impressions: The Musical except to note that it starred the exceedingly pretty Farley Granger as Mr. Darcy and the sufficiently handsome Polly Bergen as Elizabeth Bennet,2 and if it had never crossed your mind that a singing Elizabeth Bennet would be a distinctly American baritone, you might want to check out the show’s original cast recording.3

Oh, yes, leave us not forget: Hermione Gingold, as Mrs. No First Name Bennet, gets a rather, I think, spectacular joke in her comedic lament “Five Daughters”:

For years and years we prayed for a son

And oh how frustrating this is.

We tried and tried and tried and tried.

Five tries.

Five misses.4

But let’s get back to lowercased first impressions, which I was contemplating the other day as I found myself rewatching for the umpteenth time—and for no better reason than that I get a kick out of it—the Munchkinland sequence of The Wizard of Oz. This was certainly my initial exposure to the word “aver,” even if quite a few years, and a dozen or two viewings, passed before my ear finally caught up with and caught on to the lyric “As coroner / I must aver / I’ve thoroughly examined her.” I’m not sure what, as a six- or seven-year-old, I thought “must aver” was besides5 a trio of impenetrable and perhaps nonsensical syllables of a piece with “the kitchen took a slitch,” though I’m sure I doted on the follow-up “And she’s not only merely dead / She’s really most sincerely dead,” which is funny even if, or perhaps especially if, one is a six- or seven-year-old.6

I’m not sure how it works for you, but I’ve often found over the decades that certain words attach themselves permanently in my mind to first—or at least prominent and distinctive—uses. I can’t, for instance, think of “mendacity” without thinking of Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,7 in which the word pops up nearly a dozen times.8

BRICK: Have you ever heard the word “mendacity”?

BIG DADDY: Sure. “Mendacity” is one of them five-dollar words that cheap politicians throw back and forth at each other.

BRICK: You know what it means?

BIG DADDY: Don’t it mean lying and liars?

BRICK: Yes, sir, lying and liars.

And “unspeakable” can never, for me, be separated from Mia Farrow’s incantation of it in the film of Rosemary’s Baby:

Monsters, monsters. Unspeakable, unspeakable.9

The curious word “fastnesses” will always call to my mind Elia Kazan’s superb film of Betty Smith’s great American novel A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, in which I surely first heard it—

I got some French rolls, a whole half a broiled lobster from the shores of Maryland, fried oysters, caviar from far-off, sunny Russia, and cheese from the mountain fastnesses of la belle France.

—and just as surely had to look it up. A “fastness,” for the record, is “a secure or fortified place,” “a stronghold.” Lovely word, no? I like to think of the film’s husband and wife screenwriters, Tess Slesinger and Frank Davis, happening upon the word in Smith’s novel, circling it, and then, perhaps like me having had to look it up, deciding to make memorable use of it.10

I’m always happy to confess that a good bit of time passed before I realized that three particularly luscious words in Stella Gibbons’s Cold Comfort Farm, quite possibly the funniest novel I’ve ever read, were not, as I assumed, obscure (at least to me) British terms but words that Gibbons had simply made up: “sukebind” (a kind of plant), “clettering” (the act of scraping dirty dishes with a thorn twig, even if the novel’s intrepidly do-gooding heroine, Flora Poste, attempts to persuade Adam Lambsbreath, the novel’s woebegone cletterer, that “a nice little mop with a handle” might be more efficient), and “mollocking” (the chief pastime of the novel’s horniest character, Seth Starkadder,11 and it means precisely what it sounds like).

Though having belatedly twigged to Gibbons’s wee jokes, I found myself, reading for the first time Russell Hoban’s postapocalyptic Riddley Walker—

On my naming day when I come 12 I gone front spear and kilt a wyld boar he parbly ben the las wyld pig on the Bundel Downs any how there hadnt ben none for a long time befor him nor I aint looking to see none agen. He dint make the groun shake nor nothing like that when he come on to my spear he wernt all that big plus he lookit poorly. He done the reqwyrt he ternt and stood and clattert his teef and made his rush and there we wer then.

—assuming that the word “pong”—

The black leader gone in to Bernt Arse mazy ways and parbly keaping down wind of the out poast them dogs pong hevvy even when theyre dry but when theyre wet it pernear knocks you over. That smel plus the dead town pong it aint like nothing else.

—was, like Gibbons’s coinages, one more instance of Hoban’s artisanal bespoke mumbo jumbo and not simply, as I eventually learned, an (actual) informal Brit word for “stench.”

Fool me once, twice, perhaps thrice . . .

The Usual Fine Print

Thank you for being here, thank you for following, thank you especially for subscribing. All of this substackery of mine is free and will remain that way, which means that if you have chosen to contribute to its and my upkeep,12 in larger or smaller ways, you are doing something you don’t have to do, which makes your generosity that much more resonant, and I am profoundly grateful. If you’re not yet part of that contributing crew and there’s a part of you that’s thinking “Who would have thought that apostrophes and commas could be so much fun?” and you choose to join the crew, I will be eternally (or at least monthly or annually) in your debt.

Benjamin

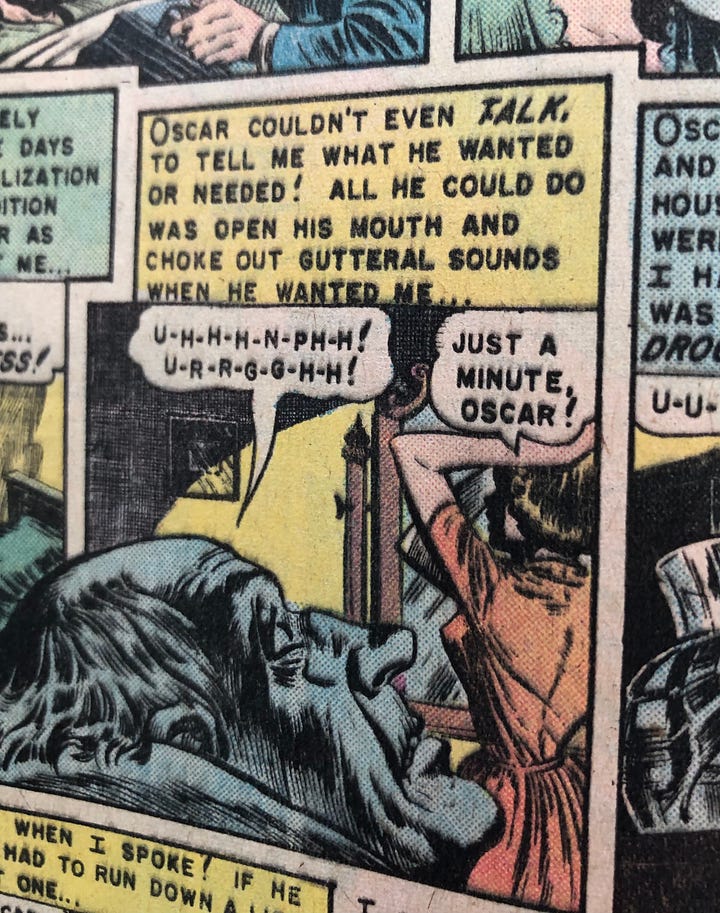

P.S., and apropos of nothing in particular except that writers do need to be reminded of it from time to time, the word is not “gutteral” but “guttural.”

As, of course, it’s not “miniscule” but “minuscule.” But you knew that.13

Here’s a footnote rerun for you, because I can’t resist:

I love “ur,” which is a kind of scholarly wackadoodle way to say primitive, or original. One often sees it capitalized, which may have something to do with its origin in German, because you know how those people like to capitalize things, but as someone who would lowercase “weltschmerz” and “weltanschauung,” to say nothing of “schnitzelbank,” because though they may derive from German and certainly look German, I happen to be speaking English, I would also lowercase “ur.” Also, if you cap it, people may think that you’re alluding, biblically, to Ur of the Chaldees, which you most certainly are not.

If Edgar Allan Poe’s is the most misspelled author’s name in Western literature, surely Bennet is the most misspelled fictional name in Western literature. Not Allen, not Bennett.

Dept. of If I’ve Told You Once, I’ve Told You A Thousand Times: Movies have soundtracks; stage musicals have cast recordings.

Hiring the thoroughly larger than life Hermione Gingold to play Mrs. Bennet was certainly apt to make First Impressions a show about Mrs. Bennet—perhaps more accurate to say that it was going to make First Impressions a show about Hermione Gingold—and it’s a clever conceit of the show that Mrs. Bennet thinks the show is about her too.

Anyway, here’s Hermione:

Because I caught myself about to make an extremely common prose error right before I posted this essay: “Besides” means “other than”; “beside” means “next to.”

Neither could I quite make out what the Munchkin barrister exclaims after the Munchkin mayor declares “Then this is a day of independence / For all the Munchkins and their descendants!” What I eventually realized he exclaims is “If any!,” which I suppose is an appropriately lawyerly thing to exclaim.

At least I was quick enough to apprehend “Oil can what?”

I recall being told once that Williams never referred to his plays except by their full titles. Never “Cat,” always Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Never “Streetcar,” always A Streetcar Named Desire. Fair enough, they’re superb titles.

As a copy editor I’ve often found myself advising writers that they’re overdoing it on certain pet words, but Williams is making pointed thematic use of the word “mendacity,” and truly he had, at his best—and his best was pretty damn best—a keen ear for repetition. Even his one- or two- or perhaps three-offs—“Christian martyr” in The Glass Menagerie, “Napoleonic Code” and “Tarantula Arms” in A Streetcar Named Desire—penetrate the brain, at least my brain, and stay there forever.

Like most of the best lines in Roman Polanski’s screenplay—in fact like nearly every line in Roman Polanski’s screenplay—“Unspeakable, unspeakable” comes straight from Ira Levin’s novel, which I think can never be praised sufficiently for both its unnerving plot and its gorgeously characterful dialogue.

“A whole half a broiled lobster”—did you notice that? I think it’s great—is a perfect bit of phrasing for the impoverished waiter Johnny Nolan.

Flora Poste! Adam Lambsbreath! Seth Starkadder! What marvelous names! Though can any of them quite compare to that of the novel’s matriarch, Aunt Ada Doom?

Just nod. I can’t see either your furrowed brow or your begrudging “aha” face.

I can't hear the word tantamount without hearing Christine Baranski saying "Tantamount! Tantamount!" in House of Blue Leaves.

Ah, Uncle Bundel.