[originally published July 16, 2024]

“All New York stories become real estate stories.”

—David Denby

A thing I like to do of a morning, while I’m glugging down coffee and trying to get my brain in gear to perform whatever tasks need tasking that day, is hop over to Wikipedia to see whose birthday it is. Once upon a time this was in part a professional obligation, as I was running a Twitter account (separate from my personal one, that is) whose chief handy hook was birthdays, but in truth it’s a thing I like to do, and still do, because it amuses me, because it gives me the chance to celebrate people I like (particularly if they’re dead actresses) by posting about them at Bluesky (on whose shores I and other Twitter refugees have washed up) or Facebook, and because it inspires me to think about people I might not have otherwise thought of, people whom perhaps no one might otherwise be thinking of on their birthdays or on most other days, and perhaps it rouses their shades momentarily and makes them smile.

In any event, July 13, just a few days ago, was the birthday of the actor Sidney Blackmer, whom, if you recognize his name at all, you might most likely recall for his having played Roman Castevet in the 1968 film of Ira Levin’s 1967 novel Rosemary’s Baby.1

Now, it doesn’t take much for me to go off on twelve rhapsodic tangents about Rosemary’s Baby, a novel I love that inspired a film I love,2 but rather than re-create each of those tangents here (perhaps I should write a book called Twelve Ways of Looking at Rosemary’s Baby; I’m led to believe that people have built entire careers on this sort of thing), I’m merely going to re-create one of my pet tangents (which itself includes, unsurprisingly, a few subtangents).

Here’s the novel’s opening paragraph.

Rosemary and Guy Woodhouse had signed a lease on a five-room apartment in a geometric white house on First Avenue when they received word, from a woman named Mrs. Cortez, that a four-room apartment in the Bramford had become available. The Bramford, old, black, and elephantine, is a warren of high-ceilinged apartments prized for their fireplaces and Victorian detail. Rosemary and Guy had been on its waiting list since their marriage but had finally given up.

The ears of certain readers, by which I mean mine, might well prick up at the mention of the distinctively named Mrs. Cortez. In Mark Robson’s 1943 film The Seventh Victim (which I might more accurately describe as Val Lewton’s 1943 film The Seventh Victim, as Lewton, the producer of a string of superb little low-budget thrillers at RKO in the 1940s, including Cat People, I Walked with a Zombie, and The Leopard Man, is always his films’ firmest creative hand, no matter who the credited director is), the actress Evelyn Brent plays a Mrs. Cortez—Natalie Cortez, in full—an embittered one-armed former dancer (how she came to become one-armed we are not told) who is variously shown playing the piano and shuffling cards with her remaining intact hand.

Oh, right, my point: The Seventh Victim is a film about a coven of Satan worshipers in modern Manhattan. Whaddya know. So let’s perhaps assume that Ira Levin was not unfamiliar with it. Let’s perhaps also assume that Natalie Cortez, by now (Rosemary’s Baby is set in 1965) a still-vital septuagenarian, eventually found her niche in real estate. One can’t, after all, spend all one’s time playing the piano, shuffling cards, and worshiping Satan.

In the film, the role of the Bramford is played by the Dakota, that majestic heap at the corner of Central Park West and Seventy-second Street.

Ira Levin’s Bramford, however, is not the Dakota; it’s not even on the Upper West Side.

So let’s figure out what and where it is.

The first key thing we’re told about the location of the Bramford is that the kitchen of the apartment being scoped out by Rosemary Woodhouse and her actor husband, Guy3—they’re about to break the lease they signed for that apartment in the geometric white house on First Avenue, you can bet—has “a window on Seventh Avenue.” Moreover, we’re told, the building’s entrance (or at least one of its entrances) is also on Seventh Avenue.

“I could walk to all the theaters,” Guy comments, which begins to narrow the geography a bit, presuming that Guy is not a dedicated urban trekker. So let’s presume that we’re north of Times Square and, perforce, south of Central Park,4 OK?

Narrowing the geography even more narrowly: Rosemary and Guy, having viewed the apartment and exited the Bramford, walk “slowly uptown along Seventh Avenue” to the Russian Tea Room, where they order “Bloody Mary’s [sic, I’m afraid, in both editions of the book I have handy] and chicken salad sandwiches on black bread.”

With the Russian Tea Room nesting cozily on Fifty-seventh Street just east of Carnegie Hall, we now know certainly that the Bramford is (a) on Seventh Avenue, and (b) south of Fifty-seventh Street (and probably not terribly far south of Fifty-seventh Street; there’s likely a limit to how far even a young, vital couple will stroll for a chicken salad sandwich).

Rosemary’s author friend Hutch, it should be noted, isn’t keen on the Bramford. “It’s where the Trench sisters performed their little dietary experiments,” he comments, “and where Keith Kennedy held his parties. Adrian Marcato lived there too; and so did Pearl Ames.”5

Hutch offers three other (nonfictitious, as it happens) buildings for the Woodhouses to consider instead: the above-noted Dakota, the Osborne (which sits at the northwest corner of Seventh Avenue and Fifty-seventh Street), and the Wyoming, which, he thinks, is “in the same block” as the Bramford. The Wyoming, one notes, is at 853 Seventh Avenue between Fifty-fourth and Fifty-fifth streets, so presuming that Hutch’s impression is accurate (or close enough for horseshoes and hand grenades), we’re now on the verge of definitively siting the Bramford.

What else does Levin tell us? Well, Rosemary finds “a Chinese laundry on Fifty-fifth Street for the sheets and Guy’s shirts,” and though we’ve already secured the neighborhood, this is getting us ever so much closer to X marks the spot. Doesn’t everyone seek out the Chinese laundry for the sheets and their actor husband’s shirts that’s closest to home?

And here’s Rosemary, quite a few pages later, looking out a window and waiting to see Guy, who’s just exited their apartment on his way to take a head-clearing stroll, emerge onto the street. And yet: “She waited and watched but he didn’t come out. He must have used the Fifty-fifth Street entrance.”6

Ding ding ding. We’re now inarguably smack dab in a building set on one of the four corners of Seventh Avenue and Fifty-fifth Street.

Yet further on in the book, sealing the geographical deal, Hutch phones Rosemary and informs her that he’s “around the corner at City Center picking up tickets for Marcel Marceau.”7 City Center, to be sure, is on the north side of Fifty-fifth Street midway between Sixth and Seventh avenues.

Hutch, then, was more correct than he knew about the closeness of the Wyoming and the Bramford. Visit, if you can, the intersection of Fifty-fifth and Seventh and do a big Mary Tyler Moore twirl (hat tossing optional). The Bramford isn’t simply on the same block as the Wyoming; it is, with a lovely bit of sleight of hand on Ira Levin’s part, the Wyoming itself, old, elephantine, gold rather than black, spooky as literal hell, and renamed, and it looks like this:

It’s also, I’m amused to note, directly down the street from my former Random House office, on Broadway just north of Fifty-fifth Street.

Department of The Fine Print

Here we are, Substack essay number 24.

Thank you for being here, thank you for following, thank you for subscribing. All of this substackery of mine is free and will remain that way. Which means that if you have chosen to contribute to its and my upkeep,8 in larger or smaller ways, you are doing something that you don’t have to do, which makes your generosity that much more resonant. I am profoundly grateful. And if you’re not yet part of that contributing crew and there’s a part of you that’s thinking “You know what? I like this fellow” and you choose to join the crew, I will be eternally (or at least monthly or annually) in your debt.

Have a swell rest of the day.

Benjamin

To be absolutely honest, the only reason I didn’t include the name of the film’s director above is because I didn’t want to write the stuttering “for his having played Roman Castevet in Roman Polanski’s 1968 film” etc. But as long as we’re down here, and as long as a chief subject of the last couple of weeks (beyond, that is, an assassination attempt, which possibly you’ve heard sufficiently about) has been the revelations of the abuse suffered by the daughter of writer Alice Munro, and of Munro’s response to that abuse, I note that the overlap of art and artist is a subject that’s been much on my mind, though I confess up front that I have no great insights to offer. I will, though, admit that I have been known to make allowances for creative works I admire created by people I do not, to put it mildly, admire, and that takes in not only Roman Polanski’s films but quite a lot of Woody Allen’s, at least those from before, let’s say, 1994, when they were still good. Perhaps you do this too (though I assure you I’m not inviting you into complicity with me; I’m merely noting). It’s a tricky thing to navigate, and maybe it doesn’t say great things about my sheepish eagerness to make compromises to satisfy my own whims, but there it is. Sincere horror + time = “context” and “distance” and “a sense of proportion,” I suppose, and if one can nowadays guiltlessly read the works of, to name just two of my favorite writers, both of whom were monumentally wrongdoing—again, to put it mildly—people, Charles Dickens and J. M. Barrie, I suspect that it’s in great part because they’ve both been dead for a long time. Eventually everyone is dead for a long time.

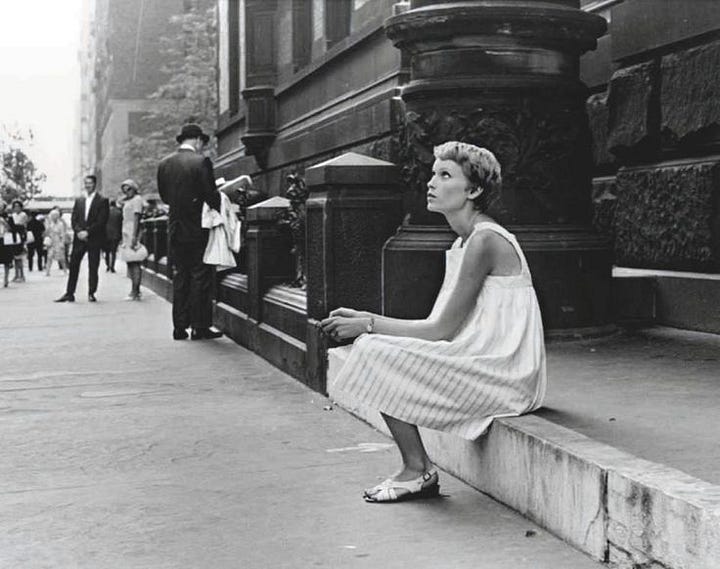

What, you thought I wasn’t going to provide a photo of Ruth Gordon as Minnie Castevet, Roman’s wife? Perish the thought. Here she is, with, to be sure, Mia Farrow as Rosemary.

And here’s a super-cool on-set shot I hadn’t seen before today, featuring John Cassavetes (as Guy), Mia Farrow, Sidney Blackmer, the great Ruth herself, and Roman Polanski.

“He was in Luther and Nobody Loves an Albatross,” Rosemary explains in an ostensibly throwaway line of Ira Levin’s somehow so memorable that any number of my acquaintances can recite it from, indeed, memory at the drop of a hat, “and a lot of television plays and television commercials.”

Perforce south of Central Park because Seventh Avenue stops at the south border of Central Park (resuming at the north border as, since 1974, Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard).

It’s a marvel the way these names are evoked with little to no additional explanation (you will never learn a thing about Pearl Ames besides her name, nor more about Keith Kennedy and his parties, though you will certainly hear quite a lot about Adrian Marcato and . . . well, never mind), as if Guy and Rosemary (and by extension the reader), like all clued-in New Yorkers, know who these people are, as one would recognize the tabloid-familiar names of, say, Homer and Langley Collyer, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, or Kitty Genovese without needing to be told anything more about them. Also, “the Trench sisters” is just g.d. brilliant.

Spoiler alert: He’s lying.

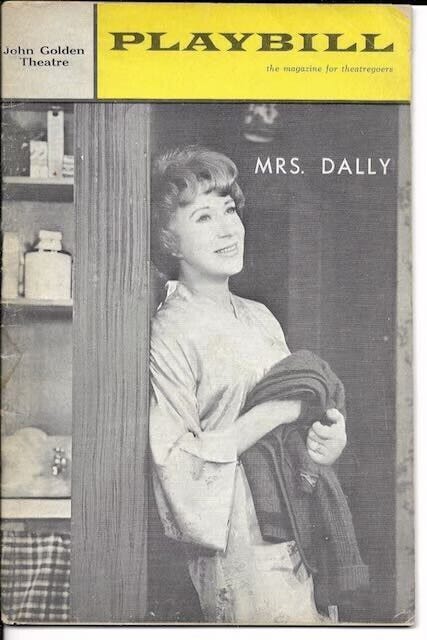

If that’s not a lovely snapshot of New York City in the mid-1960s, I don’t know what is. I’d also note that Marcel Marceau was indeed performing at City Center in late 1965, precisely when Hutch is picking up his tickets. Levin is marvelously accurate (copy editors love this kind of stuff: looking things up in hope of catching an author in an error and then delightedly not catching an author in an error) about his theatrical mentions throughout the novel, also alluding to other real-life 1965 attractions including the Julie Harris vehicle Skyscraper, Drat! The Cat! (a failed musical for which Levin himself wrote the script), and William Hanley’s play Mrs. Dally, a preview of which Rosemary and Guy attend on Friday, September 17, two days after the show had indeed commenced previews.* And now I must, for mysterious and contractual reasons, show you here the Mrs. Dally playbill, featuring its star, Arlene Francis.

*Was September 17, 1965, indeed a Friday? You bet it was.

Sure, bamboozle me with an unexpected photo of the world's best dog at the end of your text!

You'll get no sensible comments out of me today.

Thank you for the yummy essay and the photo of Sallie. Claire Dederer's "Monsters" was, I thought, a very good rumination on the difficulty of asshole artists and our ongoing love of their work. Can't speak to the copyediting.