Adventures in Proofreading (part 2)

[The Adventures Continue]

So where were we?

Oh yes.

We were in our Lilliputian studio apartment on West Twenty-third Street in Manhattan, at the fold-up bridge table we usurped from our parents that serves as our desk, and we were doing a freelance proofreading job.

My little pride-and-joy Staples electric pencil sharpener is nearby, and everything around me is increasingly covered with red or green (depending on my mood) pencil dust, as am I.

And it’s 1992 or so.

We’ve already done the proofreading part of the proofreading job, making sure that every precious word in the manuscript has made its way properly to the page proofs, and perhaps we’re particularly pleased1 with ourselves because we caught a few things that eluded the copy editor, to say nothing of the writer,2 including, besides3 a handful (or two or five or ten handfuls) of dropped or repeated words, misplaced or missing commas, a parenthetical aside that commences but never concludes, and the occasional sentence that doesn’t terminate with any terminal punctuation at all, a reference to the F. Scott Fitzgerald novel Tender is the Night that should of course be Tender Is the Night,4 and a The Beautiful and the Damned that should of course be The Beautiful and Damned,5 to say nothing of an assertion that the 1968 Democratic National Convention took place in Chicago at the Cow Palace, which is on the one hand funny but on the other hand wrong.6

Now comes the fun part.

The mechanical stuff.

Happily, I’ve been sent, as often but not always, a proofreader’s checklist, with the expectation that I’ll not only do all the tasks listed on it but check them off as I do them. Because that’s why they call it a checklist.

And here are some of those tasks:

• Check the running heads. (Remember, besides the Maine,7 the running heads? We were talking about running heads last time.) And that includes making sure that all the left-hand running heads are consistently on the left-hand (even-numbered) pages and the right-hand running heads are consistently on the right-hand (odd-numbered) pages, because sometimes they can suddenly flip positions. And of course you want to make sure that the running heads calling out a book’s chapter titles, if that’s the running-head setup, actually progress chapter by chapter, because sometimes a chapter title running head can drag into the next chapter for a few (or a lot of) pages.

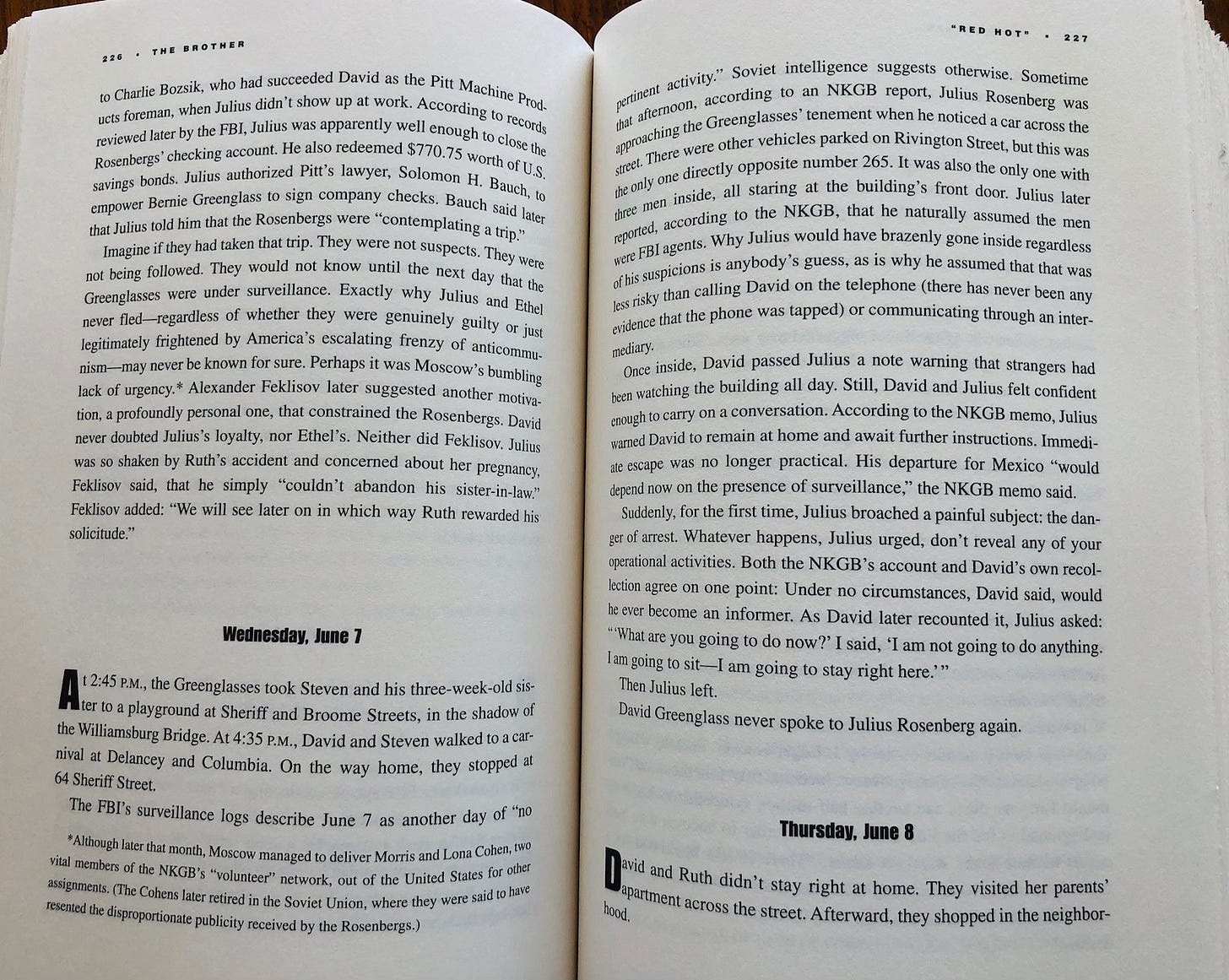

Oh, here’s, let’s look at a for-instance spread,8 as a for-instance.

In this case we’ve got the book title on the left (by the bye, this is Sam Roberts’s superb The Brother: The Untold Story of Atomic Spy David Greenglass and How He Sent His Sister, Ethel Rosenberg, to the Electric Chair)9 and the chapter title on the right. Check. Check.10

• We also need to make sure that the chapter titles as they’re given in the running heads match the chapter titles as they’re given at the beginning of each chapter, to say nothing of matching the chapter titles as they’re given up front on the contents page11 (or, for some longer books, contents pages). And we also want to be sure that the chapters are numbered consecutively, with no numbers skipped or repeated.12

• As well, we’ve filled in, on that aforementioned contents page, the page numbers of each chapter’s start, replacing the 000s that were set as placeholders, no matter that the page numbers may change again before the book goes to press as the pages continue to be revised and adjusted.

• And did we check each and every page number in the book, from first13 to last?

Yes, we did.

Well, this seems a nice place to pause. (I don’t want to wear you out.)

Next installment: those widows and orphans I promised you last time, to say nothing of bad breaks and the answer to the perennial question “How many lines of text must there be on the final page of a chapter?”14

To be continued.

Thank you all for being here, and thank you, especially, to subscribers, and to paying subscribers. I quote, again, my friend the superb Connie Schultz: “You don’t have to pay to read my writing. I understand that not everyone can do so, and I am grateful to those of you who do because you make it possible for me to keep writing.”

Sallie is grateful too.15

Alliteration alert! I could have fixed that, of course, but sometimes I like to leave glitchy things behind to see whether you’ll notice them. After all, we’re trying to build better writers and copy editors here; we’re not (why are we talking in the first person plural* today?) doing this for our health.

*I have more than once lately seen “we” referred to as the second person. No. “We” is the first person plural. The second person is “you.” As in, off the top of my head, “You are not the kind of guy who would be at a place like this at this time of the morning.”

As a proofreader, copy editor, production editor, copy chief, managing editor, etc., I have always insisted that the buck stops with me, and that if there’s something wrong in a published book, it’s my fault. It’s even all my fault. Authors are often very sweet about making that “any retained errors are purely mine” speech, but . . .

Confusables alert: “Besides” is other than, “beside” is next to. I think/fear that people sometimes erroneously regard “besides” as a downmarket version of “beside,” an even poorer relation of “anyways” and “irregardless.” Nay! It’s its own word, and a good one!

Just because a word is short doesn’t mean that it doesn’t, in what we call title case, warrant an initial capital letter. We may lowercase, in titles, little supportive words like “by” and “of” and “the,” but heavy-lifting words like “Is” (and its siblings “Am” and “Are” and “Be”) get capped.

I’m not thinking of any book in particular right now, but I’m sure that these errors, or errors very much like them, turned up in more than one job I did back in the day. Proper nouns have a tendency to go awry: Right this second I’m recalling a book I proofread in which the title of a particular essay by Sigmund Freud was rendered, from the book’s first page to its last, in a half dozen slightly different versions. Are there no copy editors?, you may be exclaiming. (Are there no workhouses?) Who knows what might have happened in this case: Sometimes copy editors aren’t given sufficient time to do their job properly, or a repeated query goes ignored, or the author rewrites half the manuscript after the copy editor has completed their task and everyone’s in a rush to get to pages and bound galleys and so a whole lot of mess is left behind, or the copy editor just blinked and missed something, as we all do (though not, hopefully, a half dozen times). (Or the copy editor’s just not very good at their job. That’s not, sorry to say, not a possibility.)

The 1968 Democratic National Convention took place at Chicago’s International Amphitheatre. The Cow Palace is an indoor arena in Daly City, California, just on the cusp of San Francisco. And though it would be amusing for Chicago to possess a convention center named after (I’m inferring the author’s stumbling free association) the mythical O’Leary bovine, it doesn’t happen to be the case. By the way: I’m not making this up. I did stumble upon such an error in a set of pages I was proofreading in the earlyish 1990s, and I certainly pointed it out. For reasons entirely unknown, the error was retained in the finished book, where I believe it still persists after numerous reprints some thirty-odd years later.

Or the Rhine, for you Anna Russell aficionados.

A left-hand page and a right-hand page, viewed as a unit.

Now, that’s quite a lot of subtitle, but when you break it down, it does everything a solid nonfiction subtitle is supposed to do: In this case, it tells us who the book’s subject, David Greenglass, is/was (atomic spy), it identifies Ethel Rosenberg (key, or at least keyer, name recognition here, you want her name on the front jacket) not only by name but, to be sure, by her relationship to David Greenglass, scarcely self-evident (if you don’t already know who they are) as they don’t have the same surname, and it lays out the grisly endpoint of the narrative (electric chair) that is the reason you’re grislily eager to read the book. I’m sure that, at the time I was working on The Brother, I took it upon myself, entirely unasked, to see whether I could whittle a few words out of the subtitle, and eventually I was sure then, as I’m still sure now, that it can’t be done.

By the way, I have a semi-jocular compulsion, every time I see or refer to a book whose subtitle includes the phrase “The Untold Story of,” to yowl: “But it’s not untold! You’ve just told it! You’ve told it right here in this book!,” and I don’t want to disappoint you or myself by not yowling it here. That said, in all my years at Random House I somehow never managed to get a subtitle adjusted to “The Hitherto Untold Story of.” Oh well.

But, again: Check them all.

The heading on a contents page should be, please, Contents, not Table of Contents.

Shouldn’t that all happen automatically? Well, that would sure be nice, wouldn't it.

Here’s a little bit of trivia for your pursuit: The first actual text page of a Random House book—well, such was the case when I began at RH in October 1993, and such was the case when I left in December 2023—is not page 1. It’s page 3. Page 1 is either what’s known as the second half-title page (a page on which only the title appears, sans subtitle; the first half-title page came, well, first, at the very start of the book’s frontmatter) or the first part-title page (if a book is indeed divided into parts; a book should have a second half-title page or a first part-title page, not both). Now you know.

Oh, OK, fine: Five.

Here’s Sallie, a few years ago, doing her imitation of a Francis Bacon painting.

The Cow Palace story is amazing and funny. "Grislily" is hi-larious.

I have been searching, in a lazy way, for a World War II film I saw on Channel 9 (or could it have been Channel 11?) in the New York area, in the 70s. An enlisted man, possibly in the Pacific Theatre, had had a brilliant battle plan that he offered up to the beleaguered captain, one that could turn the battle around, in favor of the Americans. How could he have ever had this original thought? It turns out that in his civilian life the enlisted man had been a typesetter, and he remembered the idea from a book he had typeset. Did you see this movie? What a hero. This is pretty obscure, but I thought you, of all people, would like to see someone would made books help the good guys triumph. Thanks!