Dash it all!

[of humans, bots, and punctuation]

[originally published 2 June 2025]

It’s been lurking in the background of my consciousness, like the irksome buzzing of a lightbulb that’s contemplating burning out, or a faint bad smell, source unknown: the assertion floating about that the use of what editorial types call em dashes and normal people call, well, dashes—and, contrary to legend,1 em dashes were not named in honor of Emily Dickinson’s using so many of them—is an AI/ChatGPT tell.2

I haven’t, to be honest, been keeping up intimately or deeply with the whole AI/ChatGPT foofaraw; I don’t, bless me, have to.3 The people who are interested in the work I do, and the people I work with, are not, I’d like to believe, and do believe with some certainty, the sort who enlist bots to provide their thoughts, or to organize their thoughts, or to rewrite their thoughts into the style of some other writer’s thoughts, or to devise scene-setting descriptions they can’t be bothered to devise on their own. The people I know are writers, not content creators.

Be that as it may, I try to know, in the immortal words of the immortal Miss Peggy Lee, a little bit about a lot of things, so let me race ahead in my usual semi-half-cocked fashion, and we’ll see where we get.

“Working with a student on her story,” an online chum noted yesterday, “I recommend using an em dash. She says she can’t, because professors will think she’s using AI.”

“My daughter,” another chum echoed, “was worried this week that her prof would think her essay was AI-written.”

So yes, sure, I’ve been hearing this for a little bit of a while—the use of em dashes equals bottery—but (a) whence does the accusation derive?, and (2) is there any truth in it?4

A little thoughtful googling led me to a few reputable-looking articles from reputable-seeming sources suggesting that the accusation—which I’m now promoting to calumny—is essentially social media blather, and if there are charts and graphs and proofs and other bits and/or bobs of evidence to back up the j’accusing, I can’t find them.5

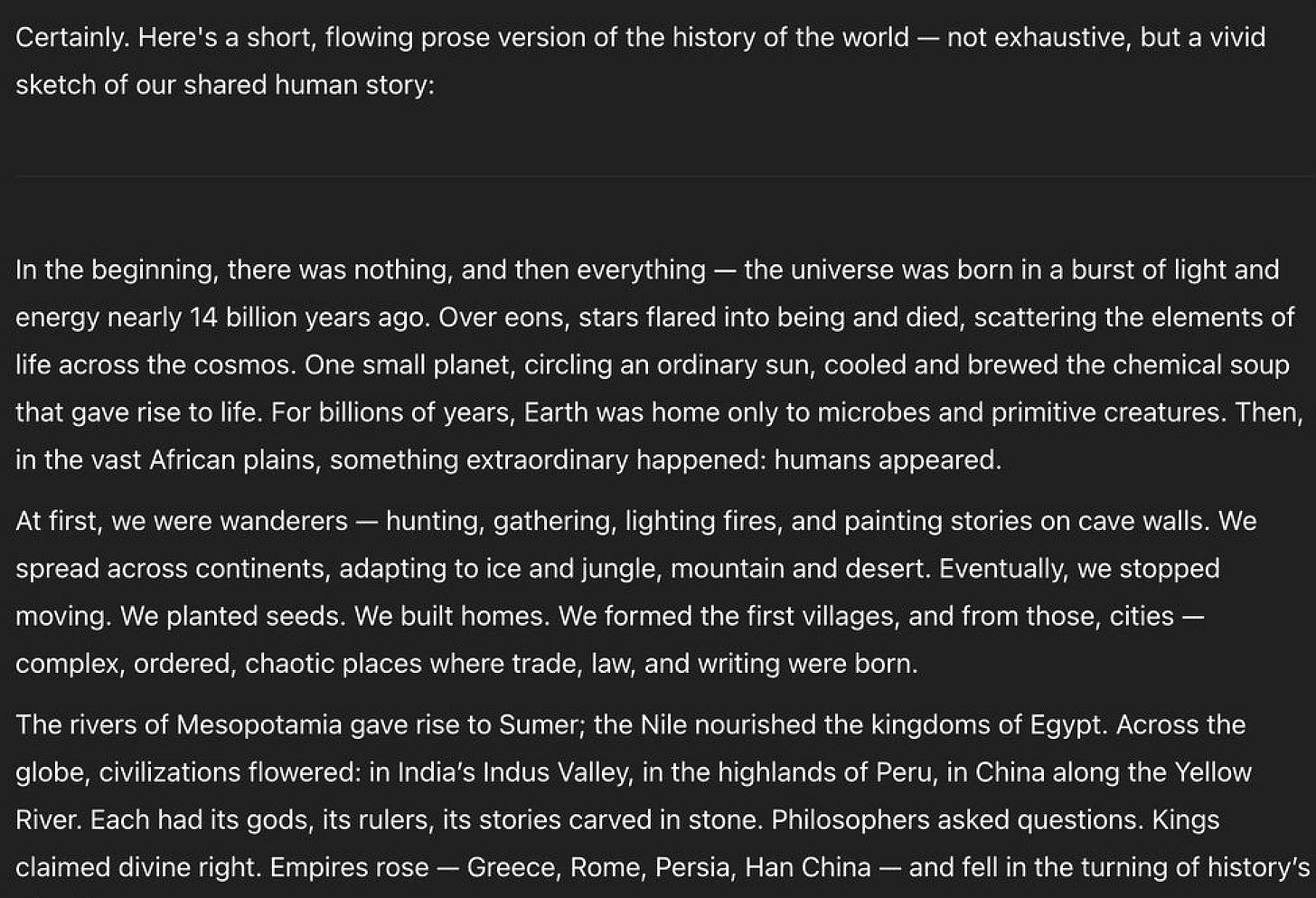

I did, however, put out a general request for a sample of bot-authored prose that might (or might not) demonstrate a passion for em dashes (I wouldn’t even begin to know how to secure such a thing), and I was graciously given this:

Dash #1: Fine.

Dash #2: Meh. I might have gone with “In the beginning, there was nothing, and then everything: The universe was born” etc. (Also, below, I’d like a capital H in “Humans appeared.” Someone should teach the bots that full sentences after colons begin with capital letters.)

Dash #3: Fine. It could be a colon too, but it doesn’t have to be.

Dash #4: Fine. What’s wonky here is the punctuation just before the dash. That should be “We formed the first villages and, from those, cities.”

Dashes #5 and #6: Fine and fine. That’s what em dashes do, baby. That’s why we have ’em.

Basically: That’s not a lot of em dashes over the course of thirteen lines, and there’s nothing weird about their use. If this were human writing, I wouldn’t bat a human eye over it.

P.S. The writer bot, at least in this case, favors the sawed-off dashes that I would call en dashes, with spaces on either side; perhaps the bot is a Brit bot.

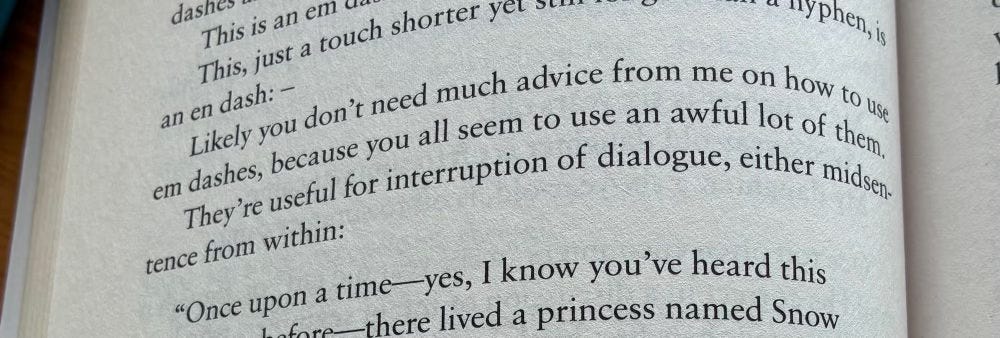

It irks me no end,6 I must note, that well-intentioned and presumably honest students (and others) should have to spend an iota of an atom of a second second-guessing their writing for fear that someone who might as well be brandishing a divining rod or a planchette is going to indict them for cheating over the wielding of a piece of punctuation so utterly commonplace that, as I joked with dead seriousness a few years ago, “you don’t need much advice from me on how to use em dashes, because you all seem to use an awful lot of them.”7

Not only utterly commonplace, I note, but utterly useful. Dashes—which isolate, highlight, emphasize—serve a very different purpose than do parentheses (which confide, like a character in a Restoration comedy stepping down to the footlights, curling a hand around their mouth, and giving the audience the good goss about what no one else on stage can, per convention, hear) or commas, which, among their many purposes, are useful for bracketing supplemental and/or useful, but not necessarily necessary, information.

Writers shouldn’t, I think, have to concern themselves that their use of em dashes raises questions about their integrity or humanity; they should simply use dashes because they’re useful, like apostrophes, semicolons,8 and the letter t.

If you have any questions, or any desire for me to continue flogging this moribund horse, or if you want a note from me to hand to teacher, let me know in the comments. I’m around.

Oh, and: Happy Pride Month.

Bonus copyediting bit o’ fun, because the subject was just raised elsewhere:

“If Howard Hughes were alive today, he would not make the list of the top five weirdest billionaires.”

“Were” or “was”?, I was asked.

“Were,” I say.

Though some people avoid the subjunctive mood entirely—and when I was a baby copy editor, back in the Precambrian Era, I was advised not to impose it on writers who don’t themselves naturally use it, which is interesting advice I don’t always adhere to, but it’s something to keep in your brain—I find it useful in the laying out of situations that are not merely not the case but truly improbable/fantastical/impossible. If you can insert an “in fact” into your sentence, you’re probably better off with (or at least can get away with) “was.”

The Fine Print

My usual—though never casual—gratitude to those of you who subscribe, and particularly to those of you who have stepped up to support me financially. It’s something you don’t have to do, so that you do it means a lot to me.

B

A legend I just made up.

I adore the noun “tell” (in its non-moundy sense, that is), and I’m thrilled that it’s busted itself loose of cardplay so that we can all enjoy and use it!

If you’d held a gun to my head, I could not have told you till I looked it up just now that “GPT” stands for “generative pre-trained transformer,” and I still don’t really know what that means, do you? Also, as long as we’re down here: if AI is human-imitative, surely it’s sourcing its passion, if indeed it possesses a passion, for em dashes from the actual human writers it’s imitating (by which I mean stealing from)?

Though I was, yesterday evening, shown a chart that seems to demonstrate a positive bot mania for the word “delve.” Go figure.

Another conversation, another day.

Hear hear! Also, from the faculty perspective, it irks me no end that all this AI whatnottery forces me to spend far more than an iota of an atom of a second second-guessing the lovely prose of students whom I generally presume are honest and well-intentioned, simply because occasionally one of their peers will turn in something in a style so dissimilar from earlier work that the reason seems obvious. And then nagging doubts creep in. Every new tool for plagiarism and cheating creates new problems, but this one is particularly insidious because it's not strictly plagiarism and thus much harder to prove. And also because I WANT my students to be beautiful writers. And I WANT them to be striving for that. And I WANT to believe in them. And I hate that this "tool" is causing them to doubt their own capacity to learn so much that they stifle their own process.

I asked my editor to change something from dash to a parentheses to make it feel more intimate and am now feeling smugly Dreyerian about it.