[originally published March 5, 2025]

The other day, in between doing chores and preparing not to watch the Oscars, I realized, still and all, that if I’d seen a film in the last twelve months made after 1968 I couldn’t tell you what it was, and I rectified that by summoning up Conclave, presumably the sole entry on this year’s AMPAS Best Picture nominees roster that might conceivably have been made in, in fact, 1968.

It was just the treat I needed—cushily well-crafted scenes of never more than moderate length, its cast of old-school actors enunciating so precisely that I didn’t, for a change, need to resort to closed captioning, a series of regularly detonated plot twists (one of them literally), and I couldn’t help but be amused to watch a two-hour film about the Catholic Church that displayed not an iota of an atom of interest in matters of faith, dogma, or spirituality—and I would not have begrudged the splendid Isabella Rossellini, as Sister Agnes, a Best Supporting Actress statuette for her parting-shot fuck-you curtsy alone.

[Oh, which reminds me: A spoiler, vague and allusive as spoilers go, but still, lies ahead, so if you’ve yet to see Conclave and prefer your surprises entirely nonpredigested, you might want to stop reading now and return sometime in the future.]

Afterward, I indulged in one of my favorite mental parlor games and decided, what the heck, to indeed premake Conclave in 1968, aspiringly with David Lean or Carol Reed doing the directorial honors, though I fear that we might have to cope instead with the journeyman, and that’s putting it kindly, Charles Jarrott, just about to embark back then on a soporific triple play of Anne of the Thousand Days; Mary, Queen of Scots; and the Burt Bacharach–Hal David–Larry Kramer1 musicalization of Lost Horizon.

Let’s cast, shall we?

To be sure, we’ll need Paul Scofield, relatively fresh off A Man for All Seasons, as Ralph Fiennes,2 and I’ve rather got my heart set on Richard Widmark as Stanley Tucci, Burt Lancaster as John Lithgow, Roscoe Lee Browne as Lucian Msamati, and the inevitable Hugh Griffith as Sergio Castellito.

(One desperately wants to find a role for Charles Laughton, but unfortunately he’s been dead since 1962, so even a quick supine3 cameo at the film’s opening is probably—probably, not certainly—beyond him at this point.)

As to the enigmatic Cardinal Vincent Benitez—wisely cast in the IRL Conclave with the unknown (and luminously magnetic) Carlos Diehz—I suspect that in 1968 we’re going to have to rethink the film’s climactic revelation with something moderately less climactically revelatory, and I’d imagine that, if you’ve already seen the film, you’ll do the same retrofitting as I’ve done,4 and someone get Franco Nero’s agent on the phone, I’m thinking.5

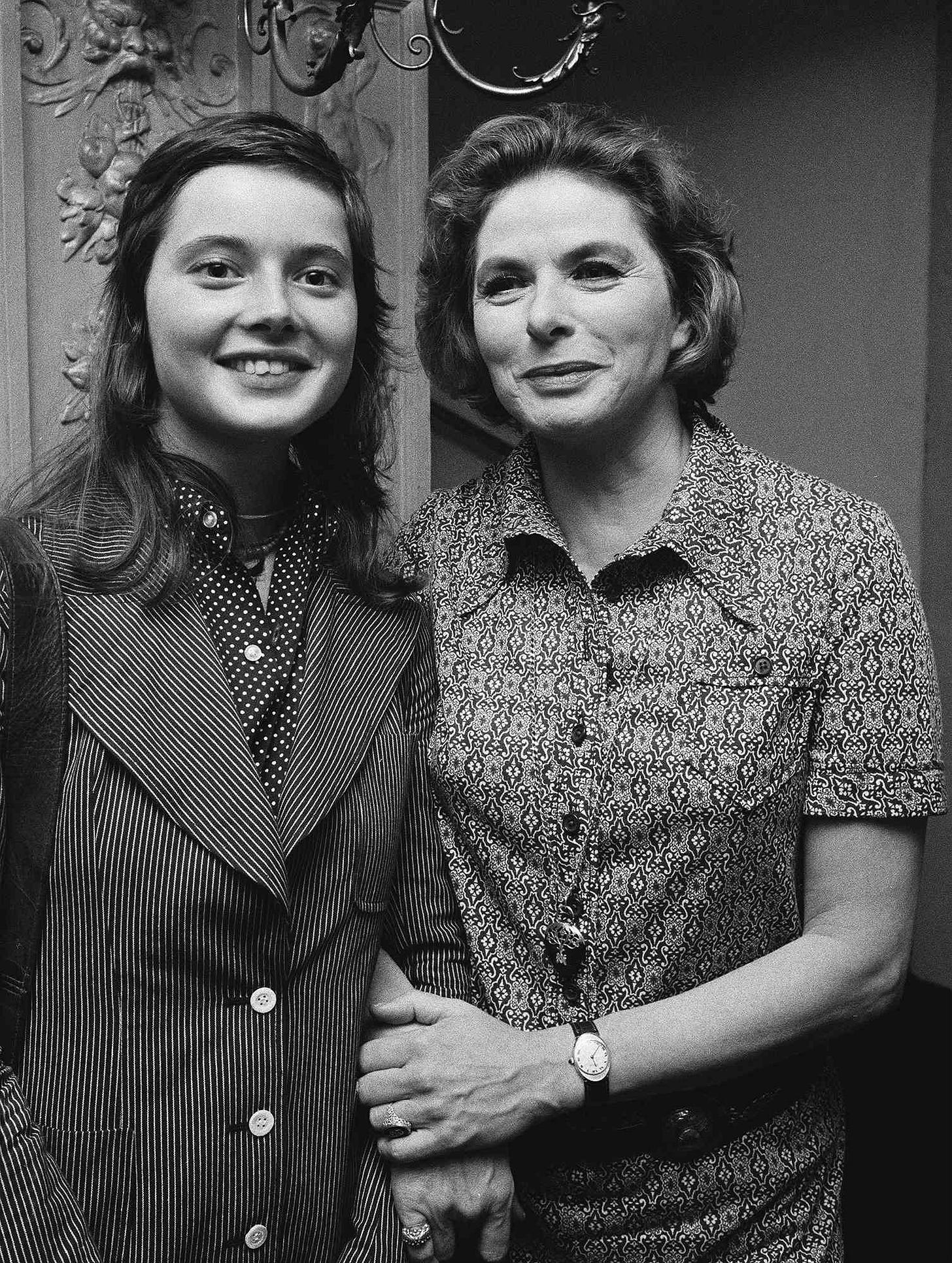

And Sister Agnes? I immediately had my heart set on Giulietta Masina, so invested was I, in my rotisserie league moviemaking, in getting Signora Fellini into a big-budget English-language film and copping her an Academy Award, till a friend pointed out that the quicker and more efficient daydreaming route would be to simply cast Isabella Rossellini’s mum, Ingrid Bergman.

Well, sure, if that’ll be easier for everyone.

Our current reality offering little by the way of amusement or solace, I’m happy to regularly nose around in the past—and not even the real past, simply a reconfigured alternate cinematic realm—fantasy within fantasy within fantasy—that I can manipulate like some sort of private puppet theater.6

Friends and I have been known, for instance, to film Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express in 1935, when the novel was still warm from the printing press, and again in 1945 and yet again in 1955 before letting the property sit dormant in preparation for Sidney Lumet’s impeccable 1974 version.7 (The trick is to induce the aforementioned Mr. Laughton to play Hercule Poirot in all three pre-Lumet versions; beyond that you’re on your own, though do consider, for the ’55 version, helmed no doubt by Billy Wilder, Rosalind Russell as Mrs. Hubbard,8 Audrey Hepburn as Mary Debenham, and Edith Evans as the Princess Dragomiroff.)

And I’ve always been mentally heavily invested in a 1941 MGM film of Anton Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, directed by George Cukor and starring Greta Garbo as Lyubov Andreievna Ranevskaya (she’s too young for the part, really, but screenwriters Ben Hecht and John Lee Mahin will figure it out), stalwart George O’Brien reinvigorating his career as the upwardly mobile Lopakhin, Aline MacMahon as poor put-upon Varya, Bette Davis (on loan from Warner Bros.) in a piquant cameo as Charlotta, Judy Garland as Anya, W. C. Fields (puckishly billed as William C. Dukenfield) as Gaev (can’t you imagine the imaginary billiard shots?), Harry Davenport as Firs (it’ll be Lionel Barrymore over my dead body, and also Lionel’s), S. Z. “Cuddles” Sakall as Simeonov-Pishchik, Buster Keaton as Yepikhodov, an almost unrecognizable Joel McCrea in bedraggled whiskers and spectacles as Trofimov, and baby Anne Baxter as Dunyasha.9

Perhaps I’ve thought about this too much.

Please feel to correct my casting in the comments!

Big thanks to my pal David Benedict for the unwitting loan of this party piece’s title.

As always: Thank you all for being here, and thank you, especially, to subscribers, and especially especially to paying subscribers, who make it possible for me to keep writing. I’m utterly in your debt.

Sallie is grateful as well, though, for the moment, not unlike Greta Garbo, she wishes to be left alone.

Yes, that Larry Kramer. Also: en dash alert!

Post-publication addendum: It’s been pointed out to me that Paul Scofield played Ralph Fiennes’s father in Quiz Show. To be fair (to me), that was nowhere in the forefront of my mind during my retrorecasting, though who knows if it was lurking in the back of the shop somewhere with the rest of the accumulated junk. I landed on Scofield, I swear! (or I swan!, as some folks say), purely because he struck me as the proper Classy Thespian of Appropriate Age for the part in the late sixties.

Lest you feel bereft at the absence of copyediting wisdom in this entry: Please, please, please remember that people who are lying on their backs are supine, not prone, and if mnemonic devices work for you (I myself can never remember them), you can probably get supine/spine into your head, yes?

If you’re indeed thinking what I’m indeed thinking, it’s perhaps not such an exceedingly gasp-inducing revelation for a member of the Catholic Church clergy in 1968 (or 1868 or 2028), but I’m sure that audiences of the time will be impressed. Unless you’re contemplating that we might go full Pope Joan here, but . . . nah.

You were expecting perhaps Anthony Quinn? Cantinflas? Warren Beatty in his Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone bronzer? No.

More copyediting: Noting the rule—well, more of a guideline or understanding than a rule—that one should never use more than two em dashes in a single sentence, I note as well that it’s a rule to be occasionally broken, a guideline to be occasionally erased, an understanding to be occasionally disunderstood.

I give the subsequent David Suchet Orient Express telefilm credit for its full immersion in the collective grief that motivates the plot, which the Lumet version largely and glamorously skims over and past and around, and to be sure, Suchet is the Hercule Poirot of one’s dreams, or at least of mine. I give the Kenneth Branagh videogame version no credit at all.

Full credit to my friend Jon Maas for that inspired bit of casting. I long to hear Roz bray “For pete’s sake, what’s a drachma?”

Back to real life, though a bit later than 1941, the writer Garson Kanin, at least according to Garson Kanin, had his eye on Greta Garbo for precisely this project—or, should I say, had his eye on this project for, precisely, Greta Garbo: “I was among those who tried to lure her back to the screen. My idea was to do a production of The Cherry Orchard, with her as Madame Ranevskaya. During our first meetings, she surprised me with her wide knowledge of Chekhov and his work. We talked it out for months. I never got her beyond the ‘perhaps’ point, and in time the idea melted away. . . . Looking back, it is easy to see why she occupied a place of her own on the film scene. There was only one Garbo. And she, alas, gave up.” (This quote, an excerpt from Kanin’s memoir Hollywood, at least as I find it reproduced online—accurately, I hope; I don’t have the book to hand—was brought to my attention long after I first started musing on my Chekhov’s Back and Garbo’s Got Him vehicle. Funnily enough, if Kanin had managed to coax Garbo out of her semi-unintentional retirement, it’s entirely possible that the film’s director would have been Kanin’s frequent collaborator [drumroll] George Cukor, who had already directed the actress in Camille, not to mention her accidentally final film, that cataclysmic bore Two-Faced Woman. What do I win?)

If anyone reading this has NOT seen the 1974 "Murder on the Orient Express," please just watch it for Wendy Hiller alone. All the rest is wonderful gravy.

What I wouldn't give to watch your Cherry Orchard. But a quibble. Benitez seems to me to be the very incarnation of faith and spirituality, while letting sleeping dogmas lie.