Off the Rails

[because sometimes bad things happen to good writing]

For the last two weeks I have been talking about copyediting so much—in online seminars, in correspondence, and, in my first, and whirlwindingly quick, visit back to the Random House offices at 1745 Broadway since I retired at the end of 2023, in person1—that, in all honesty, I’m a bit sick of the sound of my own voice, and that takes some doing.

That said—and said, and said, and said—I’ve been intrigued to note that a recurring question in these sessions has been:

What happens when copyediting goes wrong?

With the appropriate follow-up question:

And what do you do about it?

As long as the writing of books and the copyediting thereof remain human endeavors, and I have no reason to think that, the depredations of the various plagiarism machines we’re having relentlessly stuffed down our windpipes lately,2 that will ever meaningfully change, that very human factor will occasionally, despite our best efforts, lead to things going not as we would have them go.

Good writers, I have found, like to be well copyedited, accent on “good” and “well.” Less good writers, I have also found, have been known to view copyediting—any copyediting at all—as an affront to their self-esteemed talent, and there’s not much that can be done about that except to, if properly warned, copyedit them as minimally as possible.

But sometimes the marriage of a good writer and an accomplished and well-intentioned copy editor is made elsewhere than in heaven. I have told the story—often—of a case in which one of the best copy editors I’d ever worked with in all my thirty years at Random House—a copy editor so expert that numerous top-rank writers, having been copyedited by that copy editor, would be subsequently, insistently copyedited by no one else—went off the rails on one manuscript in which, somehow, the CE couldn’t locate, much less meet, the writer’s voice on its own territory and terms and persistently, in an attempt to polish and tighten the text, which is what copy editors are hired to do, ended up dulling and flattening and otherwise deflating it, including demonstrably (and this is always the awfullest thing, short of inserting actual errors) not getting the jokes.

Well. The writer was justifiably choleric, the writer’s editor summoned me, as departmental copy chief, for a wee confab, and we quickly decided that the only possible recourse was to have the manuscript entirely recopyedited by someone else—which, happily, putting the foot on the gas pedal somewhat,3 we had just enough time to manage in the usual race to get to typeset pages and bound galleys.

To be sure, we never told the original copy editor about the crisis. There was, I thought, no point: The copy editor had never delivered less than stellar work before and, I was sure, would never deliver less than stellar work in the future (and never, so far as I know, did). Something this one unlucky time simply went—unpredictably, unlikelily, and very humanly—awry. It happens.

It can also occur that some first-rate writers—younger debut writers particularly, not used to the process of having their work examined and responded to so minutely—will open up their copyedited manuscript Word files and feel not supported and assisted but criticized, harangued, and, worst, patronized, and such situations, uncomfortable and unhappy for everyone involved, can lead to a lot of tactful conversations that aim to unruffle a writer’s feathers without throwing the copy editor, who quite possibly did absolutely everything expected of them and did it well, under the bus. And, as long as we’re taking our imagery from birds, occasionally one finds oneself, as the intermediary, eating a goodly portion of crow.

I’m not—and I underline this point strenuously—suggesting that some copy editors can’t come off, in both their suggested changes and in their marginal commentary, as a bit, well, lofty, or worse, and this is one reason that, as part of the departmental process, Random House production editors—that is, the in-house staffers whose responsibility it is to guide a book through the copyediting and proofreading process—spend quality time reviewing a copyedited manuscript before handing it off to the editor to hand it off to the author, in the hope of catching (and mitigating, minimizing, and sometimes outright deleting) suggestions and commentary that are guaranteed to be taken the wrong way.

But again, for all the checks and balances, and for all the best attempts at attentive sensitivity, and with blessings on the collegiality, informed by mutual respect, that collaborates on repairing missteps (actual or simply perceived) rather than engaging in a lot of finger pointing, or at least not too much finger pointing, the best laid plans of mice and editorial types can, from time to time, fall wide of the mark.

And—and as much as I’m not given to “the moral of the story is”—you try to learn from what didn’t work and do better next time.

And now the usual P.S.’s and digressions:

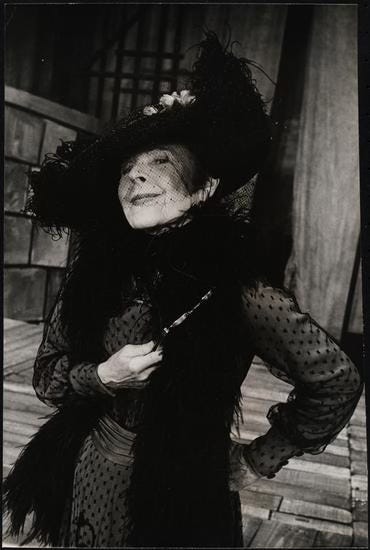

Let us celebrate today, October 30, the birthday of the great actress, playwright, and screenwriter Ruth Gordon, from whose wry mouth emerged one of my favorite quotes that isn’t “Oh, Rose, you’re so stuck up”4 or “Think what you like, Lucille”:

“I don’t know the problem with being pretentious if you can follow it up with something.”

Speaking of “Think what you like, Lucille,” I had cause recently to revisit and tout this bit of text whence it derives, from Marilynne Robinson’s gorgeous novel Housekeeping:

Lucille began swinging her legs. “Where’s your husband, Sylvie?”

There was a silence a little longer than a shrug. “I doubt that he knows where I am.”

“How long were you married?”

Sylvie seemed a little shocked by the question. “Why, I’m married now, Lucille.”

“But then where is he? Is he a sailor? Is he in jail?”

Sylvie laughed. “You make him sound very mysterious.”

“So he isn’t in jail.”

“We’ve been out of touch for some time.”

Lucille sighed noisily and swung her legs. “I don’t think you’ve ever had a husband.”

Sylvie replied serenely, “Think what you like, Lucille.”

Do note, among other things, the careful use of italics for dialogic emphasis (a well to which I think writers should be careful not to go too often) and that magisterial speech tag “replied serenely.”

I’m reasonably certain that I saw director Bill Forsyth’s film of Housekeeping before I ever read the novel—alongside David Lean’s Dickens films and the Merchant-Ivory A Room with a View, I think that it’s certainly one of the finest film adaptations of a novel I’ve ever watched dozens of times—and I will forever carry Christine Lahti’s indeed serene (and scathing) delivery of “Think what you like, Lucille” close to my heart.

Thank you for joining me here, with extra thanks to subscribers and extra extra thanks to subscribers who have chosen to support this endeavor of mine financially for no better reward than being able to kibitz in the comments. I do not ever take this for granted, and I am always grateful.

Sallie is always grateful too.

Speaking of housekeeping, a reminder that on the evening of November 10 I’ll be in supportive conversation with Dan Chaon in celebration of his wonderfully eerie and creepy new novel, One of Us, at Book Soup in West Hollywood.

And on the evening of December 15 I’ll be presiding over In the Night. In the Dark.: An Evening of Shirley Jackson Readings, courtesy of Writers Bloc Presents and starring Annabeth Gish and Kerry O’Malley. It’s going to be, if I say so myself, massive unnerving fun, and if you’re in the neighborhood of The Ebell of Los Angeles Lounge, I’d love to see you there!

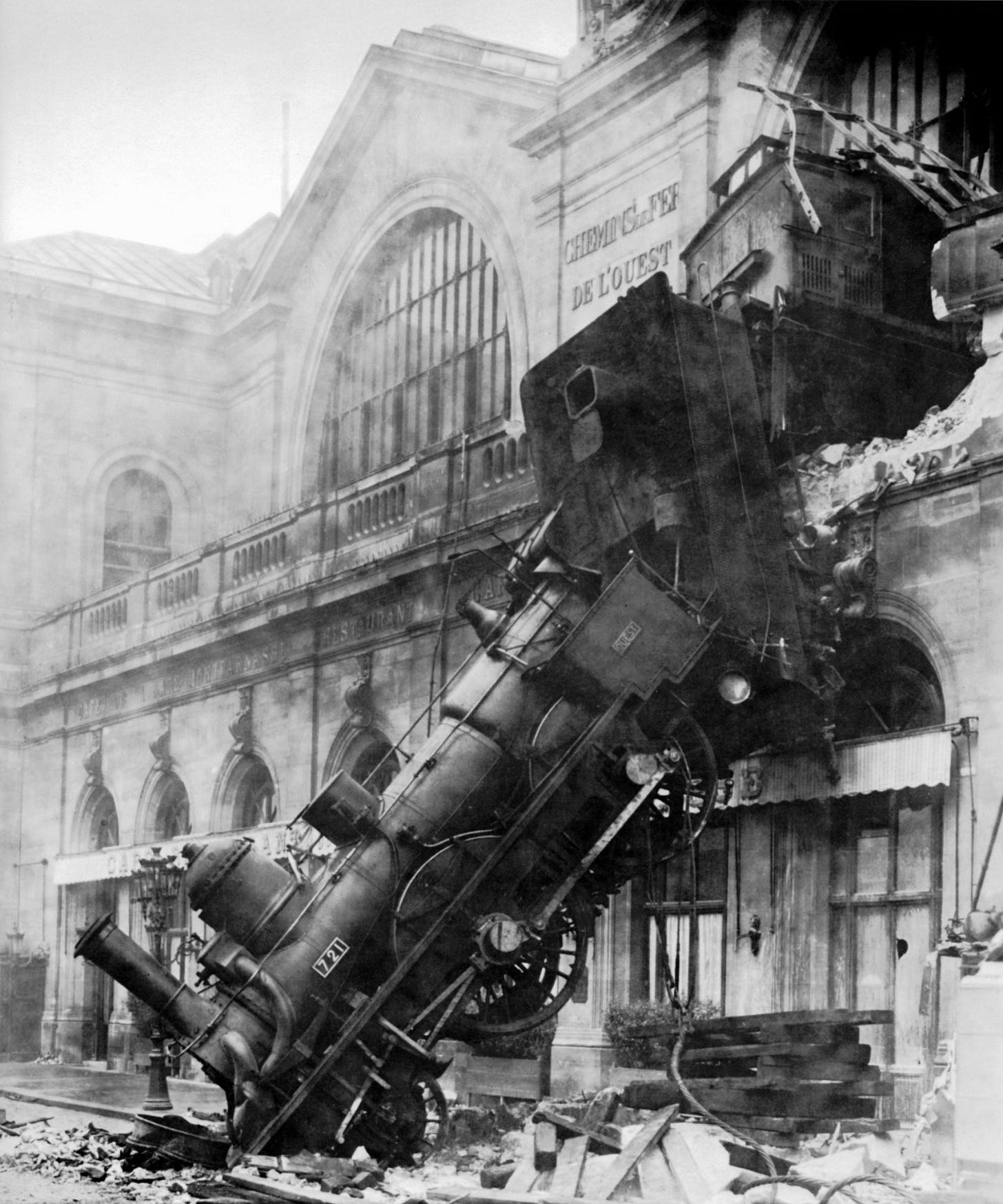

Cover photograph: The Montparnasse derailment, October 22, 1895, captured by Lévy and Sons

It was fun, if a bit startling, to be back in the building and to see so many of my former colleagues. I’ve also discovered that the answer to the self-addressed question “Do I miss New York City?” is a resounding “Not even a little.” Though, to give Manhattan its due, there’s nothing like breakfast at the Applejack at 55th and Broadway, ooh boy.

Over at Bluesky the other day, I ran across the declaration “I work for a biotech. All the managers and engineers and PhDs use LLMs on almost a daily basis, and from what I can tell it is a huge timesaver and in a year or two any professional who is not LLM-literate is going to be unemployed.”

Cool story, bro.

A lot.

God bless the great Joan Carroll, who bats that one out of the park in Vincente Minnelli’s film Meet Me in St. Louis. By the bye, that line, as well as many of the film’s other ineradicable lines that some of us dote on to the point of irrationality, derives straight from Sally Benson’s 5135 Kensington short stories originally published in The New Yorker and eventually gathered into book form by (yay for the home team) Random House.

Ah, "Housekeeping" -- what an amazing novel. I'll trust you and try the film.

Unlikelily – sort that one out, accursed Spellcheck!