“But it was an experience. How do we keep the experience?”

It’s 1990, and I’m attending an early preview of John Guare’s Six Degrees of Separation at the Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater,1 the smaller of what were then Lincoln Center Theater’s two auditoriums.2

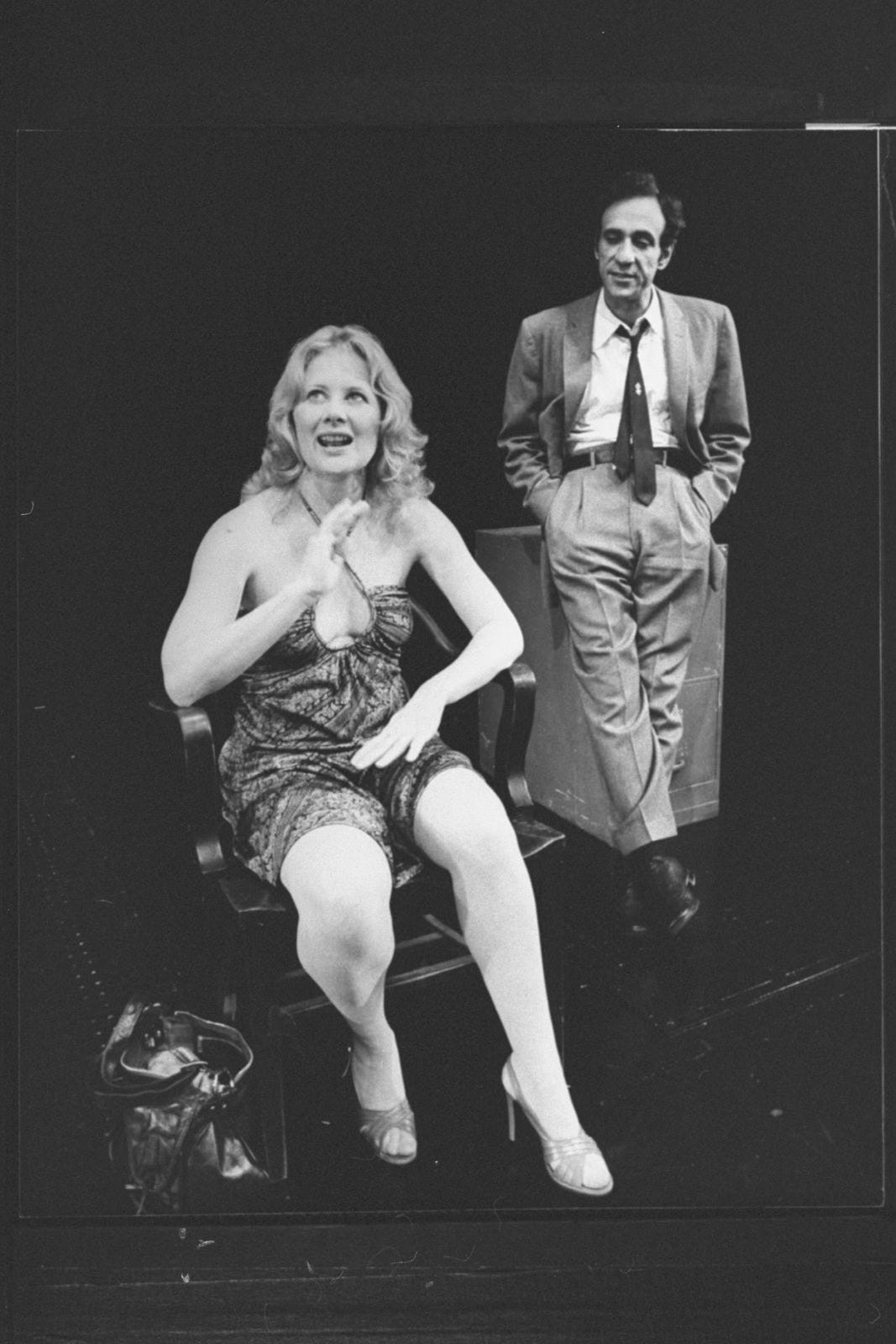

It’s a titanic play, riveting from the get-go (“Tell them!” is its alarmed first line as the lead characters, Louisa Kittredge, called Ouisa, and her husband Flan, short for Flanders, race onto the stage to, indeed, tell us), and Stockard Channing, as Ouisa, is, it’s immediately apparent, at least to me, delivering one of the great stage performances of the late twentieth century in what is, it’s also immediately apparent, at least to me, one of the great plays of the late twentieth century.3

Anyway, as Six Degrees is racing headlong toward its finish line (it might be one of the fastest plays I’ve ever seen), Channing makes an entrance in what, I can’t help but notice, is a, you’ll pardon me, unflattering column of a gown that, it seems to me, she’s not enjoying wearing. A, it makes her look rather, well, sawed-off (and though Channing is a petite 5′ 3″, she tends onstage to look, I think, majestically statuesque), B, it doesn’t move and she can’t seem to move in it, and C, it’s topped with a sort of backward chiffon shawl that she has to keep batting out of her way every time she wants to move her arms.

It’s an odd little dissonant note in what is otherwise a gorgeous production, but for whatever reason,4 it remains and resounds in my mind. Also, I think: That gown is a goner.

A few months later I return to revisit the play, which has transferred from the little downstairs Mitzi Newhouse to the bigger upstairs Vivian Beaumont (and thus, simply having levitated a few yards, has also transferred from Off-Broadway to Broadway).5

The production is much the same, with the notable replacement of the excellent James McDaniel as the interloping, insinuating Paul possibly Poitier by the excellent Courtney B. Vance. Also the same, I can’t help but notice bemusedly, is that awkward gown. Well, what do I know?, I uncharacteristically think. Also: None of my business.

A couple of months even later I return to see the play yet one more time (a visiting out-of-town friend is eager to see it, not that I need an excuse), and here comes the big scene, and . . .

Enter Stockard Channing in a gasp-worthy (and I may indeed have gasped) gown: a sculptural black velvet sheathy kind of thing that looks as if it had been constructed directly on her, with (this is all my recollection of something I’ve repeated to myself and others for decades now; I can’t seem to find any photographs of either version of the dress that quite support this extended reverie of mine; you’ll just have to trust me, or at least go with me, or not)6 jeweled shoulder straps up top instead of that mosquito net, and Channing looks marvelously, gorgeously, sexily, stellarly like (perhaps you’ve inferred this already) John Singer Sargent’s famous/notorious Portrait of Madame X.

That’s it, really, that’s the whole story.7 Though I can’t help but wonder how the dress finally got replaced.8 There’s a story I read once about Beverly Sills taking a shears to a costume she’d very nicely and very repeatedly asked to have rebuilt for her in a more Bubbles-flattering color. I won’t say that I can quite see the endlessly thrilling Stockard Channing wielding an oversize scissors, but I won’t say that I can’t quite see it either.

The End

P.S. Sometimes I think that recollections are more interesting (and perhaps more psychologically valuable and revealing, at least to and about their teller) for how one’s preserved their reality rather than for what their reality actually was, which is why I'd make a terrible journalist (though perhaps a better memoirist, at least as we’ve come these days to regard memoirs). As to this story, then: Who knows. But it’s a story. Or at least an anecdote.

Thank you for dropping by. Thank you particularly if you’re a subscriber to this series, and of course thank you especially if you’re a paying subscriber—that’s above and beyond, and I’m grateful.

If you’d like to support me in this work and would like something you can hold in your hands to show for it, do please consider purchasing a copy of Dreyer’s English or, perhaps, the Stet! game, which particularly makes a fine stocking stuffer, they tell me.

Many of the theaters in New York City, especially the venerable Broadway ones, spell their names Theatre with an -re, but Lincoln Center Theater, relatively younger, groovier, and more forward-looking, uses the relatively younger, groovier, and more forward-looking (to say nothing of more American) -er spelling. As I’ve noted a thousand times and will no doubt note a thousand times more before I take my final breath, one spells proper nouns as they desire to be spelled, and any editorial decision to ignore those proper nouns’ preferences in favor of a house style preference—as, for instance, one of our more distinguished U.S. newspapers insists on styling Broadway’s St. James Theatre as the “St. James Theater,” which is bad, and London’s National Theatre as the “National Theater,” which is not only worse but ridiculous—is ill-advised, to put it mildly.

Now there’s a third, the Claire Tow. Not germane, but I might as well finish the thought and mention it.

One of the other great plays of the late (ish) twentieth century—I always like to give it a plug in the hope of inspiring curious readers to read it—is Guare’s Landscape of the Body, which I saw at the Public Theater (another -er theater) in 1977 in a production, starring the great Shirley Knight, so preternaturally, eerily memorable that I can close my eyes even now and revisit great swaths of it. I recall someone’s remark once, long ago, that Landscape is a play that theater people will always want to revive and audiences will always revile; nonetheless, I’d like to see it produced asap with Tatiana Maslany in the lead, and I volunteer to direct it if no one else is inclined to, though someone else will have to bankroll it.

My deep shallowness, quite possibly.

Six Degrees of Separation did not win the Tony Award for Best Play that season; neither did it win the Pulitzer. Go look up what did, I dare you. It still pisses me off.

As I interrogate (sorry) my own memories, I think that there had surely to have been two dresses, even if I may be a bit off on the details, the second appearing long after it was too late to make any difference to anyone other than the person in said dresses, otherwise why would I remember this story at all?

It’s treasurable that Channing was given the chance to re-create her performance as Ouisa Kittredge in the 1993 film of Six Degrees, even if there’s a gaping box-office-mandated, I presume, hole at the piece’s center where there should be a performance. Oh well, Channing is great-beyond-great, and I can watch over and over again (and I certainly have watched over and over again) the luncheon scene in which she delivers her searing “How do we fit what happened to us into life without turning it into an anecdote with no teeth and a punch line” speech, shocking not only hostess Kitty Carlisle Hart but guest of honor Madhur Jaffrey. “These are the times,” Channing, fleeing the room, informs Donald Sutherland as Flan Kittredge, “I would take a knife and dig out your heart.” Talk about gasp-worthy.

Obviously there are any number of people who know The True Story Of The Gown (If I’m Even Recalling It Accurately), including Stockard Channing herself, costume designer William Ivey Long, and director Jerry Zaks.

There is that one moment with Stockard Channing wielding scissors to address a wardrobe situation (but as Mrs. Bartlet, offing her husband’s tie)...

This was a great post. Thanks.