The other day I realized that I was on an adroit kick. Which is to say: I was on an “adroit” kick. It had suddenly, the quick and close proximity1 of a few online examples exposed, become, apparently, the first adjective I’d reach for to describe someone’s or something’s prowess, dexterity, finesse, expertise, you get the idea. And if I wasn’t using the word “adroit” I was employing its adverbial sibling, “adroitly.”

Searching back through a year’s worth of posts I discovered that I’d used “adroit” or “adroitly” about a dozen times—not really an oppressive lot given how many words I’ve disgorged into the ether these past months, but I was happy to enlighten myself.

All writers, in my experience, have pet words that will repeatedly turn up in their work or works if they’re not paying attention. They’re tickled by the look of something, or its sound, and they simply fixate on it and keep typing it out. It’s an entirely unconscious process, and to be sure, it’s the consciousness of a copy editor2 that will, or at least might, eventually expose the repetition.3

At the dawn of my career, when copyediting occurred entirely on paper without the backup of Word files because Word files didn’t yet exist,4 the only way to uncover a repetition was (a) to notice it in the first place, and (b) to then riffle and shuffle one’s way back through a manuscript’s previous pages in search of the culprit or culprits.5

Nowadays, it’s an easy thing to search a file to scratch that sleuthing itch, but you can’t scratch the itch until it indeed starts to itch. That is, you have to notice the echoing word or phrase before you can go in search of its forebears. And even the best copy editors may not notice a repeated word or construction in the midst of doing all the other things a copy editor does in copyediting.

The manuscript for Dreyer’s English, for instance, was hugely adroitly6 copyedited, but only when I was in the recording studio narrating the audiobook did I notice that I’d used the phrase “garden variety” four or five times over the course of a not especially lengthy book. Quite possibly no one would ever have noticed, but it pleased me to be able to, admittedly at close to the last second, prune out a few of those garden varietals in both the audio and print version of the book.

Funnily enough, only much more recently was it pointed out to me by one reader—nicely, jocularly, respectfully, carefully—that I’m rather keen on, of all things, the word “festoon,” which shows up in DE one way or another . . .

Well, let’s just say: more than twice. And, really, once would have been sufficient.7

I don’t know that any writer is ever fully aware of their full arsenal of tics, habits, pet words, rote constructions, etc., and I don’t know that a writer should, truly, aspire to such extreme self-consciousness. I’d fear that it would be paralyzing to the whole process.

But it’s nice, as one can be, to be a bit on to oneself.

Speaking of self-editing, it’s a lovely thing, if you have the time, to set aside a piece of writing for a few hours or more and then head back into it with an eye toward trimming some of its fat.8 I don’t believe that good copyediting or self-editing is always a matter of delete, delete, delete—sometimes a sentence can be improved only by lengthening it, for clarity or simply to give an idea some room to breathe in—but it’s the rare piece of writing that can’t stand to have its screws tightened a bit.

As Blaise Pascal commented a few centuries ago:

Je n’ai fait celle-ci plus longue que parce que je n’ai pas eu le loisir de la faire plus courte.

Which is to say (translation/paraphrase mine):

This letter is longer than it should be because I didn’t have the time to make it shorter.

Thank you for being here, and my ongoing thanks to subscribers, with extra thanks to those of you have volunteered to support this endeavor financially. Truly it makes a difference to me, in a variety of ways. (Plus it affords you the ability to comment and/or question, and you know that if you comment and/or question I’ll comment and/or answer right back.)

Sallie says thank you too.

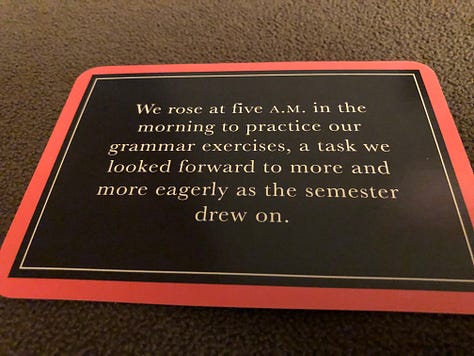

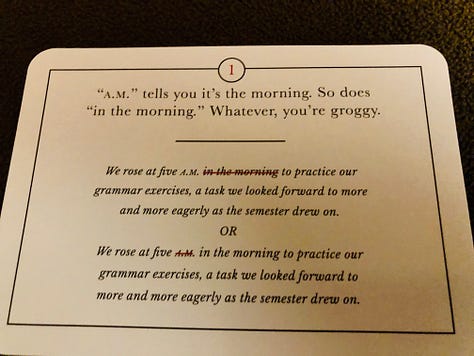

By the way, if you’re in the Greater Los Angeles area today, I’m hosting my first ever live and in person game of Stet! this evening at 7 at Village Well Books & Coffee in lovely Culver City, and perhaps I’ll see you there.

If you can’t be there tonight and wish to amuse yourself with Stet! (or a book or a T-shirt), you can certainly secure your own box.

Cover photograph: Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth in The Lady from Shanghai (1947)

Is “close proximity” redundant and repetitive? Sure it is. But it’s a thing one says sometimes, if one feels like saying it. I don’t judge. Except when I do.

Not to be confused with “the conscience of the king,” as in “The play’s the thing” etc.

To be sure, I’m not speaking of the writerly habit of plucking up a particular word and using and reusing it with good and intentional cause, as in—and this is one of my favorite passages, and speaking of repetition, stop me, or don’t, if you’ve heard this one before—this bit of text from the opening chapter of L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz:

When Dorothy stood in the doorway and looked around, she could see nothing but the great gray prairie on every side. Not a tree nor a house broke the broad sweep of flat country that reached to the edge of the sky in all directions. The sun had baked the plowed land into a gray mass, with little cracks running through it. Even the grass was not green, for the sun had burned the tops of the long blades until they were the same gray color to be seen everywhere. Once the house had been painted, but the sun blistered the paint and the rains washed it away, and now the house was as dull and gray as everything else.

When Aunt Em came there to live she was a young, pretty wife. The sun and wind had changed her, too. They had taken the sparkle from her eyes and left them a sober gray; they had taken the red from her cheeks and lips, and they were gray also. She was thin and gaunt, and never smiled now. When Dorothy, who was an orphan, first came to her, Aunt Em had been so startled by the child’s laughter that she would scream and press her hand upon her heart whenever Dorothy’s merry voice reached her ears; and she still looked at the little girl with wonder that she could find anything to laugh at.

Uncle Henry never laughed. He worked hard from morning till night and did not know what joy was. He was gray also, from his long beard to his rough boots, and he looked stern and solemn, and rarely spoke.

It was Toto that made Dorothy laugh, and saved her from growing as gray as her other surroundings. Toto was not gray; he was a little black dog, with long silky hair and small black eyes that twinkled merrily on either side of his funny, wee nose. Toto played all day long, and Dorothy played with him, and loved him dearly.

Today, however, they were not playing. Uncle Henry sat upon the doorstep and looked anxiously at the sky, which was even grayer than usual. Dorothy stood in the door with Toto in her arms, and looked at the sky too. Aunt Em was washing the dishes.

And I had to trudge five miles in the snow to school and home again, uphill in both directions.

Back then I developed—of necessity—the knack of being able to remember where I’d seen something in a manuscript—toward the top of the page, somewhere in the middle, etc. (I’m not alone in this. Other increasingly agèd copyeditorial types developed it as well.) A knack unused is a knack abandoned, but I can still rustle it up on occasion when I’m reading what we now must or at least can or may refer to as a print book and I’m trying to find something I’d read earlier.

👋🏻

Bedeck, decorate, adorn, embellish, etc. One ought not to write as if one’s gorged on a thesaurus and then hocked—or perhaps you prefer to hork?—up its contents, but I’m not above googling a word and “synonym” in search of some fresh mode of expression, and neither, I think, should you be.

Originally, speaking of which, “trimming out some of its fat.”

Speaking of writers’ tics, here’s my latest source of teeth-gritting, eye-rolling, head-slapping annoyance (and it’s doubly annoying because I don’t know what to call it): Writers, especially screenwriters, can’t string together two or three sentences without using (again, what IS this called) a format I can only describe as “The noun, it verbs.” You know, like so: “The evidence, it shows that…” and “The Senator, she said…” and “The sentence, it pains me.” My partner and I first noticed that the brilliant Rachel Maddow had become enamored of this sentence construction to the point where she could no longer utter a straightforward sentence like “The Senator said….” Then I realized that the fiction series I was reading was littered (and using it so often is a form of littering rather than festooning) with the same affected indulgence. Once or twice in a novel for emphasis? Sweet. But over and over and over? I don’t think my chagrin comes from my preference for directness; I love Byzantine sentences with scads of parenthetical asides and ancillary and explanatory clauses (and you are a master at these) delicately balanced with subject–verb simplicity. Unfortunately, now I cringe every time I hear/read “The noun, it verbs.” And I STILL don’t know what to call it. Can you enlighten me?

That said, the first thing I learned as a junior advertising copywriter is that people don’t read the copy unless attracted by the picture. And, sadly, very few memorize the material … no matter how enticing.