A few weeks ago I realized, uberdevotee of his work that I am, that I’d somehow never read (or seen) Edward Albee’s 1970 deathwatch drama All Over, so I decided to remedy the oversight by securing a copy of the script and, a few days ago, reading along with a 1976 telecast that resides on YouTube in an iffy print whose sound goes out of synch from time to time, but you know what they say about beggars and choosers.

It’s interesting—to me, at least—to occasionally watch a play (well, a video of a play; I’m not going to an actual live-actor theater with a book in my mitts, like the opera folk used to do with their libretti before proscenium-arch surtitles and chair-back subtitles showed up) with the text handy, particularly when the playwright is as invested in his stage directions and, especially, line-reading directives as Albee is.

A few of the latter, at semi-random:

(More a whine, but protective)

(Quiet, almost innocent interest)

(Almost a reproach)

(Looking about, almost amused)1

(A stuck record)

It’s also interesting—to me, at least—to observe in performance any variations between the scripted lines and the actors’ deliveries, though in this case, a handful of exceedingly trivial and presumably unintended alterations and one (surely purposely) omitted “fuck” aside, the telecast cast—shoutouts particularly to the superb Myra Carter and Anne Shropshire—was precisely letter-perfect.2

But to the point: What struck me hard, almost as soon as the figurative curtain rose, is that All Over plays (and reads) as if one had stuffed the better part of Albee’s work (particularly the earlier A Delicate Balance and the later The Lady from Dubuque and Three Tall Women) into the maw and down the gullet of the AI moloch and then asked it to vomit up an Albee script: the lengthy spoken arias that meander from A to Z and, usually, all the way back to A with myriad digressions between, the self-conscious repetitions of catchphrases and pronouncements, the characters’ little musings about and corrections of their own word choices, the bountiful expressions of regretful bemusement (“triste” is one of Albee’s line characterizations here). I (truly) burst out laughing at the moment, relatively early on, when The Daughter (that is her name: The Daughter) “rises, almost languidly, walks over to where The Wife”—that is her name, The Wife; she is The Daughter’s mother—“is sitting, slaps her across the face, evenly, without evident emotion, [and] returns to where she is sitting,” at which point The Wife, after a polite “Excuse me,” “rises, just as languidly, walks over to where The Daughter is sitting, slaps her across the face, evenly, without evident emotion, [and] returns to where she is sitting.” Surely this is the most Albee thing that Albee ever albee’d.3

Nowadays we make cracks about AI and ChatGPT; once upon a time we spoke, more simply, of staleness and self-parody.

From Walter Kerr’s extremely perceptive New York Times review:

[Albee] is off form, seriously. Having surrendered his vituperative energy, once the best thing about him, he has turned placid to no purpose but to overdecorate his prose.

The result is that almost all of the play’s speeches are self-starting; they don’t flare up naturally out of an embattled context. And we never really care who speaks next. Our heads don’t turn to a character, demanding that he make himself heard. The characters are all completed and packed away, available to us now only in prerecordings.

Staleness, self-parody, shtick: These are things I think about, fret over, fear, as a writer. Lord knows I possess more than my share of habits and tics and rituals that, left to their own devices, show up endlessly in my prose.4 How do you tell the difference between shtick and style? I don’t always know. (How happy a thing it is to have an editor.)5

Anyway, this is what I’m thinking about today: wondering first, answers perhaps later. Perhaps much later. But for now: merely wondering.

Oh, here’s a little bit, from right at the start of All Over, that tickled me, and it might tickle you as well. It’s majestically up its own ass, as much of All Over is, but it’s not unamusing (as much of All Over also is—not unamusing, that is)6:

. . . All at once he said to me, “I wish people wouldn’t say that other people ‘are dead.’” I asked him why, as much as anything to know what had turned him to it, and he pointed out that the verb “to be” was not, to his mind, appropriate to a state of . . . non-being. That one cannot . . . be dead. He said his objection was a quirk—that the grammarians would scoff—but that one could be dying, or have died . . . but could not . . be . . . dead.

Also, today’s missive was going to be all about em dashes as an alleged tell of ChatGPT-generated text7 and, more allegedness, the alleged alarming decline in the use of semicolons—but clearly I got distracted. Another time.

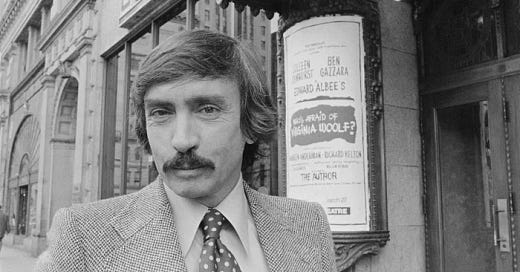

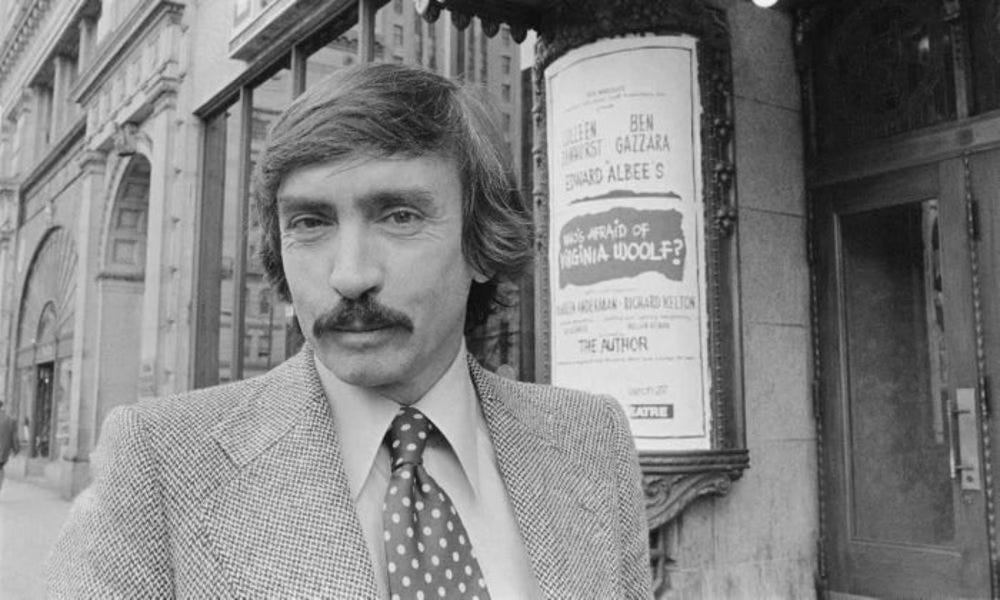

Cover photograph: Edward Albee poses in front of Boston’s Colonial Theatre during the pre-Broadway engagement of the 1976 revival of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, starring Colleen Dewhurst and Ben Gazzara and “directed by THE AUTHOR”

The Fine Print

Thank you for being here. Thank you particularly to subscribers, and if you’re a paying subscriber, additional blessings on you. I appreciate the tangible, practical support—it helps me find/make the time to do this writing—and I appreciate the support simply for its being supportive. Really, it means a lot to me.8

Benjamin

P.S. Do, if you’re so inclined, hop over to my website and check out the merch, plus information on how to purchase signed copies of Dreyer’s English (they make great Father’s Day and/or graduation presents, and time is running out!).

I’m almost sensing a theme here, almost.

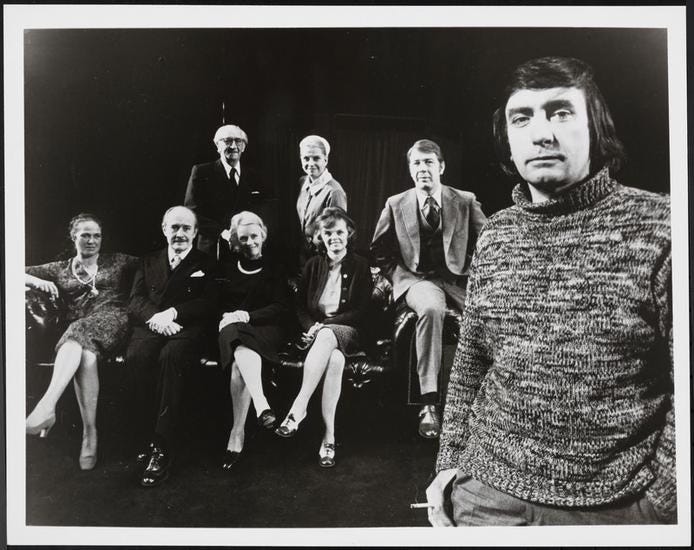

Speaking of letter-perfect, I particularly commend to you, by the bye, the 1973 American Film Theatre version of Albee’s masterwork, A Delicate Balance—and I use that comma-of-singularity pointedly; not that it’s a competition, but between the brawling, exhausting marital fisticuffs of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and the skewering, apocalyptic despair of A Delicate Balance I give the tiara to the latter. (Maybe I’m just an apocalyptic despair kind of guy.) As the formidable Agnes, Katharine Hepburn, whom perhaps you wouldn’t be surprised to find, at this late date in her career, engaging in a bit of script embroidery, bringing the character to herself as much as she’s bringing herself to the character (as she was wont to do), is faithful to Albee’s script not merely to the letters but to the very commas, which might have had something to do with Albee’s literally looking over her shoulder on the set:

Anyway, A Delicate Balance is not only my favorite of Albee’s plays but one of my favorite plays by anyone ever, and it’s so marvelously well constructed that one might not notice on an initial viewing or even multiple viewings or dozens, if you’re me, readings that the entire plot is predicated on a clearly wealthy couple’s (wealthy enough to employ servants, plural, among other things) living in a house that contains only four dedicated bedrooms and no additional guest rooms at all. But be that as it may.

It also, surely, takes stones of steel to write a character—All Over’s The Wife—who is a blatant plagiarism of A Delicate Balance’s Agnes and then hire the actress who’d originated the original role to originate the carbon copy.

Footnotes, for instance.

Also parentheticals.

A problem for me, whenever I write about Albee, is that I find myself more or less unconsciously trying to imitate him. It’s not unlike watching Bette Davis in one of her goddamn Warner Bros. epics—Mr. Skeffington, for very particular instance—and finding oneself talking like her for the rest of the day, week, month, life.

#YHGtBFKMwTS

Would the New Yorker write Albeeësque?

Hooray for footnotes and for parentheticals -- especially yours.