copyeditorial reëxamination

[further notes on The New Yorker (yes, The New Yorker)]

Yesterday’s post (mine) about that article (The New York Times’s) about that copyeditorial update (The New Yorker’s) kicked off a lot of commentary and queries, so I thought I might lasso everyone’s thoughts, and my thoughts about everyone’s thoughts, into a single place (this must be the place), with the usual additional commentary of my own.

• Ultimately it was hugely clever of The New Yorker to publicize a number of updates concerning largely innocuous but-of-course matters (changing “Web site” to “website,” “in-box” to “inbox,” etc.), while at the same time digging in their heels on some of their most, um, distinctive style points (the retained/imposed diaeresis in words like “reëxamine,”1 the by-now-unique hyphen in “teen-age”) that are so distinctly New Yorker–y2 that even people possessing only a passing acquaintance with the magazine and its foibles might well recognize them. That’s what we call branding. That’s also what we call eating one’s cake and having it too. So, y’know, kudos to them. Plus here we are talking about it.

• For the rest of the authorial, editorial, and copyeditorial3 world, though, I would advocate constructions like (because I prefer them, which tends to be my best and often only reason to advocate anything, and, less solipsistically, because they are, style-wise, invisible, which is another way of saying that they don’t scream attention to themselves, if you follow my old drifteroonie) “reexamination,” “reelect,” “cooperation,” and the like, saving any little punctuational clues and flourishes for when meaning or legibility crucially demands them, as in, say, “co-op” and “re-create,” the latter being for me a very different thing than “recreate,” though much of the world seems to have raced past me on that point. As to “website,” “inbox,” and “teenager,” those, I think, qualify as no-brainers, so save your brains re those.

• As to “Internet” vs. “internet,” I’ve addressed that previously and publicly, so let’s not belabor it now. (Or you may read up on it here, if you’re inclined. I’m sorry not to be able to offer a gift link; I no longer have a subscription to The Washington Post. Perhaps someone will share one in the comments, as generously occurred yesterday re the Times article cited above.4 And of course the less, shall we say, scrupulous among us know how to lurch behind a paywall when we need to. Not that I endorse that sort of thing. I would never.)

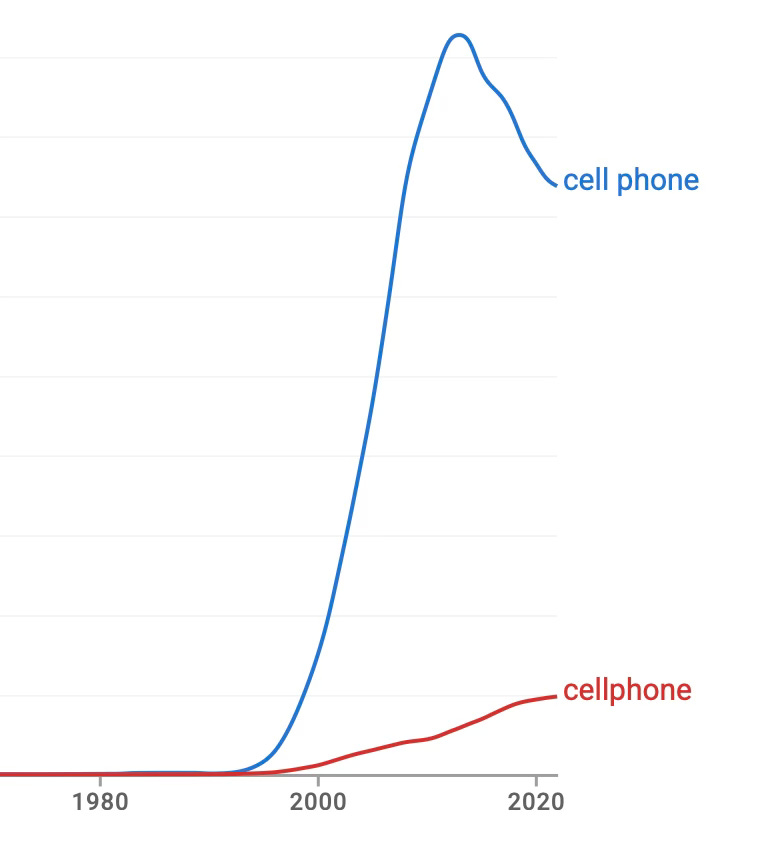

• The New Yorker’s new adoption of “cellphone” over “cell phone” tickled me, as that’s one of the rare changes I ever endorsed and campaigned for as a copy editor and copy chief simply out of sheer willfulness and not because of any observation of changes wrought in the language via writers who were out there writing in the world. I view that kind of proactiveness as, I confess, something of a copyeditorial sin—I think that copy editors should reflect rather than lead, much less originate—but I simply wanted to see if I could Make Something Happen. Results are relatively dispiriting.5

But, hey, I tried.

And, yes, as Andrew Boynton of The New Yorker acknowledged, to most people cellphones are, nowadays, simply phones (or mobiles, which is adorable and teddibly, I think, British), but so long as there remains a useful distinction, persistently in decades-spanning fiction, decreasingly in real life, between landlines and cellphones, the distinction remains, well, useful.6

• The New Yorker’s firm ongoing deathgrasp7 on “per cent” simply reminds me that if you want to go seriously old-school you’ll also retain the period (full stop) that evokes the origin of “percent” in “per centum.” That is, “In fifty-seven per cent. of cases.” (That’s the sort of thing you’ll occasionally run into in the sorts of books that also used to refer to jazz as “jazz.”) Also a reminder that in prose that’s not incessantly concerned with mathematics or money, it’s nicer to write “In fifty-seven percent of cases” (you’d certainly prefer that in dialogue) or “In 57 percent of cases” rather than “In 57% of cases.” (You’ll know when you need to resort to numerals and percentage signs, trust me.) (Or ask me.)

• To other matters: It seems (someone helpfully provided me with a confirming screenshot yesterday evening)8 that The New Yorker persists in setting a comma in constructions like “In January, 2023, four months before,” etc., to which I say: Please don’t. “In January 2023, four months before,” etc., suffices.9

• Though if they’re still doing things like “When Lynn Fontanne died, in 1983,” to make clear that Mme. Lunt died only the one time, I applaud their rigorousness but won’t mimic it. (Though I do write things like “The Cherry Orchard, by Anton Chekhov,” so I occupy my own glass house here, I suppose.)

• And let’s simply not talk about “focussed.”

One final note on house style, though not The New Yorker’s:

As I’ve often had cause to note, or simply gone out of my way to note, when I joined Random House decades ago it was made clear to me that Random House had no house style, a brisk and bold statement that was meant to mean, simply, that we were encouraged to approach each book on its own terms, not to relentlessly and unthinkingly apply our own confined sense of correctness.

Like many brisk and bold statements, it was never, and still isn’t, 100 percent true.

We maintained any number of points of house style—setting book titles in italics, for instance, not in roman and quotes (you may have noticed the reference in yesterday’s Times piece to “Dreyer’s English” rather than Dreyer’s English; many newspapers and magazines continue not to use italics any more than is absolutely necessary, certainly not for book titles, movie titles, play titles, etc.)—but they were (a) largely neutral, unnoticeable points of skeletal construction, and (b) more or less indistinguishable from everything that everyone else in book publishing was doing. So not so much house style as, simply, style.

But we were always (and I suspect/hope/pray always will be) a house of the series (serial, Oxford) comma, and it was the done thing, in copyediting, to impose that comma without so much as a by-your-leave or Mother-may-I.

It’s amusing (to me, at least) to note that 96 percent of authors put up with that comma (happily or unhappily, who knows?, but at least silently, which most of the time is at least as good), 3 percent rejected it (often loudly, and you’d just roll your eyes, mutter imprecations, and cope), and once in a blue moon an author of that mighty remaining 1 percent would actually preemptively10 advise us before copyediting even commenced to Not Even Think About It. How well I recall one of that 1 percent going so far as to adorn his book with a subtitle that actually required (at least as far as I’m concerned, to say nothing of decency) a series comma and thus conspicuously didn’t get one. And there was not a bloody thing I could do about it except to torture the book’s editor (who happened to be my editor) with my spitting distaste.

Today’s cover illustration is a snap I took years ago at London’s National Portrait Gallery. It’s, to be sure, a detail of a larger painting (also, ha ha ha, the reflected exit sign), but I can’t recall what the larger painting is, and my attempt to reverse-search the image didn’t get me anywhere. If you happen to recognize it, please do let me know down in the comments.11

And speaking of down in the comments, I do hope you’re checking them out, entry by entry here, because people hereabouts are very interesting, often offering (or demanding!) clarification on certain fine points. And I do try my best to answer all answerable questions, so: Feel free.

The Usual Fine Print

Thank you all for being here, and thank you, especially, to subscribers, and especially especially to paying subscribers. I quote my friend Connie Schultz: “You don’t have to pay to read my writing. I understand that not everyone can do so, and I am grateful to those of you who do because you make it possible for me to keep writing.”

Sallie is grateful too.

In my (cell)phone conversation yesterday with the lovely Times reporter, I went well out of my way to avoid saying the word “diaeresis” out loud, because I’m always afraid I’m going to mispronounce it. I believe I just kept referring to “the double dots.” I do, so long as we’re chatting confidentially down here in the footnotes, retain the diaeresis in “naïve,” simply because I think it’s pretty and, slightly more important than its prettiness, you can’t have “naïveté” without “naïve.” (And “naivety” is simply too tragic-looking to be borne.)

To be sure, the antique acute accents in “décor” and “début” are also pretty, but one is not Edith Wharton, is one.

En dash alert!

For the record, I favor the constructions “copy editor,” “copyedit,” “copyediting,” and “copyeditorial.” Some people like “copyeditor,” which I suppose sits nicely next to “proofreader”; The New Yorker, at least per this most recent newsletter, seems to favor the construction “copy-editing.” As the French say: Everyone has gout.

Post-publication addendum #1: And then as if by magic a kind friend offered up the gift link. Here you go!

You’d think that that would, logically, be “disspiriting,” wouldn’t you. But it’s not. Though I did find, from Jonathan Swift long ago: “It is a most disspiriting distemper.”

If you want to be a better writer, do please eschew the sorts of adorable little bloggy throat clearers and other tics that people like me resort to to be adorable, to ostensibly re-create the sound of speech, because we’re hasty and careless and self-amused, etc.: the various “um”s, “y’know”s, “shall we say”s, “well”s, etc.

If you’re in the word business, you should make up a new word at least once a month, I think, otherwise what’s the fun of being in the word business.

And thus: “‘Seems,’ madam? Nay, it is. I know not ‘seems.’”

And yet here I am, persisting in setting commas on either side of any use of “etc.”

Or, of course, preëmptively.

Post-publication addendum #2: Not to spoil anyone’s sleuthing fun, but do you know what happens when you (belatedly) google “man with hand on globe” “National Portrait Gallery” “London”? This happens:

It’s a portrait of Sir Francis Drake.

Also, the illustration made more sense before I changed the title of this post post-publication (it used to be, for no particular reason beyond my standard hubris, “The World According to Me”), but oh well, it’s still an excellent image.

And yet I cannot see "cooperation" without thinking of barrelmaking.

We need to distinguish when a footballer was resigned (I.e. disappointed) or re-signed (likely with an increase) to a contract