Too many notes?

[notes on notes]

The other day I observed, as I observe from time to time, an online brawl about the things that are often referred to, randomly/indiscriminately/lumpingly, as footnotes, and I wandered off to grab up a link to the incisive and brawl-settling essay I’d written on the subject only to discover that . . . I’d never written it. Or, if I’ve written it, I can’t find it.

So here goes.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before.

Or don’t.1

First, let’s get our terms straight.

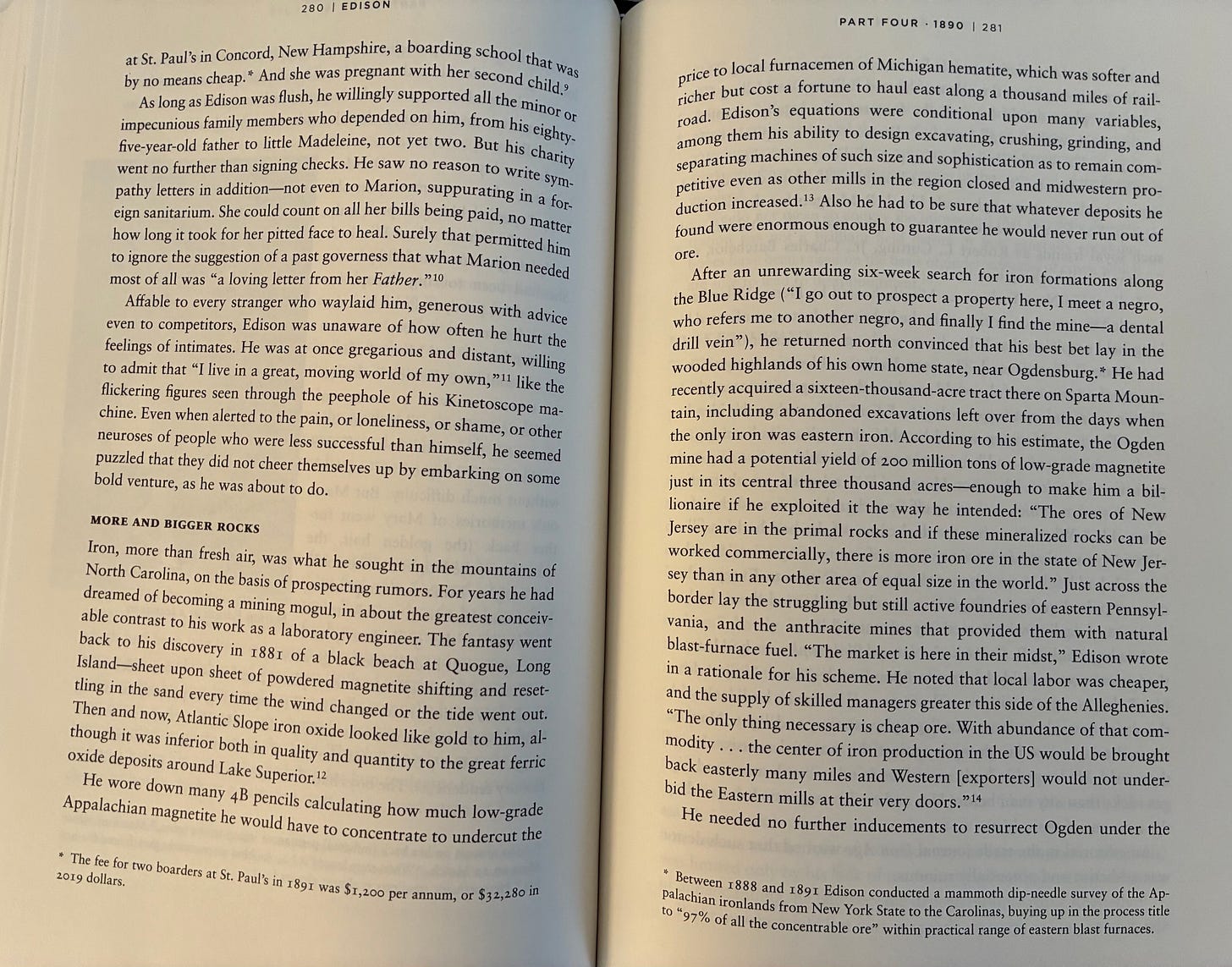

Footnotes are the things that huddle at, indeed, the feet of pages. From where I sit, footnotery is best reserved for the flotsam and jetsam of information that doesn’t quite belong in the text proper on the mainstage2 but is still helpfully amplifying, as for instance here in Edmund Morris’s splendid biography Edison (which, like Merrily We Roll Along, proceeds backward).

Of course some writers, naming no names, fetishize footnotes to the point of kink and float their text above a virtual sea of them.3

You can also see here how footnotes are properly called out by a series of symbols whose identities and order can vary, style coaching guide by style coaching guide, but I tend to like, from start to finish, asterisk, dagger, double dagger (or crossed dagger), section sign (which I tend to refer to as “thingie,” since I can never remember what it’s called), parallel lines, and pilcrow (a.k.a. paragraph sign).4

You can also also see that the symbols recommence their procession page by page.5

As to the citational/bibliographic-type notes that pile up mightily in the backs of books—and I’ve worked on books whose notes sections run far north of a hundred pages, if not far north of two hundred pages—those are called . . . notes. Or endnotes, if you must.

Those (end)notes come, predominantly, in two flavors: numbered notes, which hearken back to wee superscript numbers in the main text (as in the Edison pages shown above), and blind, or catchphrase, notes, which I’ll get to in a second.

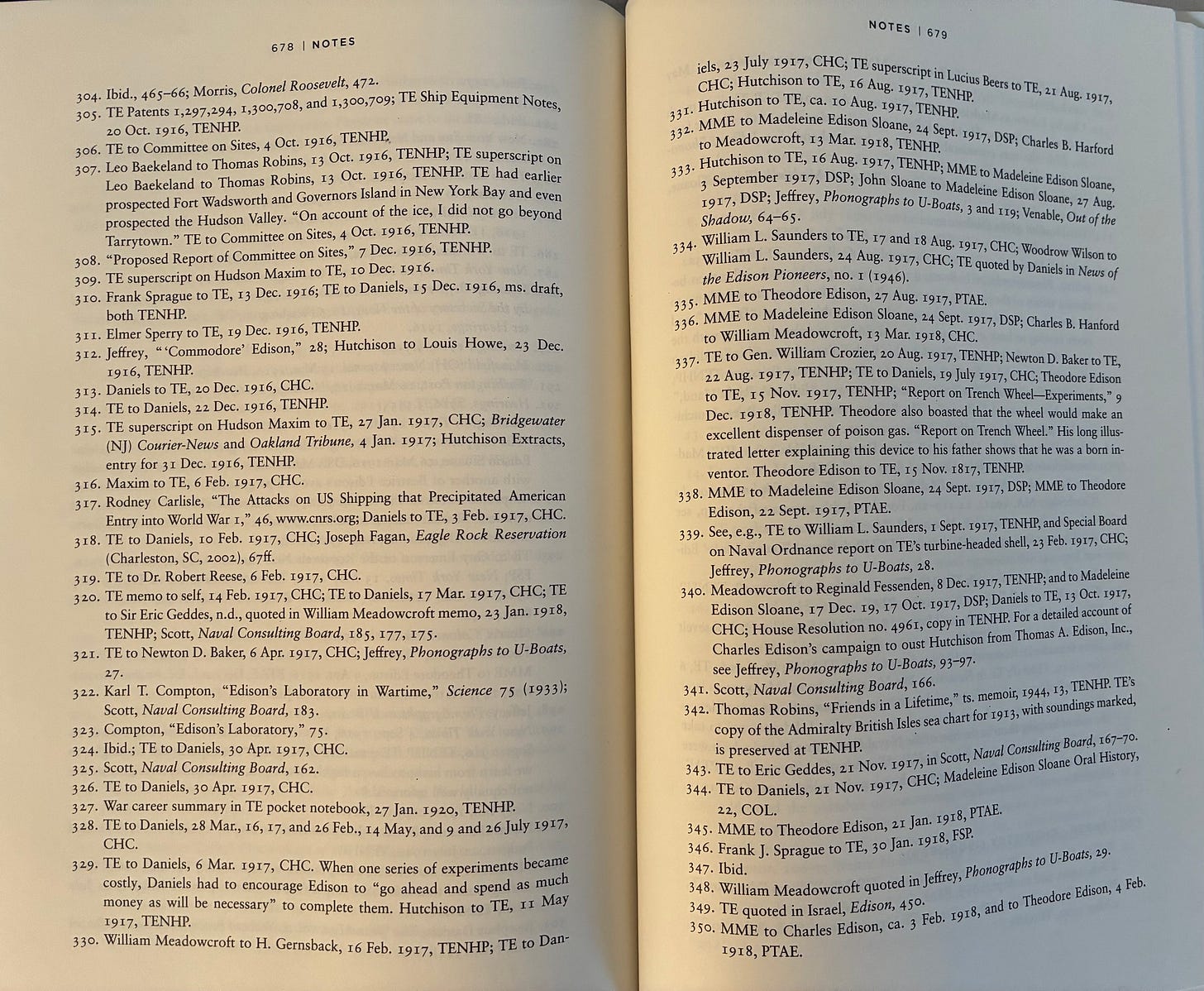

Here’s a sample spread of notes from Edison:

The author has already, to be sure, explained, at the start of his backmatter, all that TENHP TE CHC MME etc. stuff and thus saved himself, as the notes roll on and on, a lot of repetition and, certainly, a few pages.6

You can see as well how Edmund has tucked amid his citational notes niblets of information that, again, didn’t quite have a place in the main text—and didn’t even need to be read immediately as footnotes—but were simply too good to discard outright. (I always think of these backmatter niblets as a reward for readers who are brave enough to brave notes sections at all.)

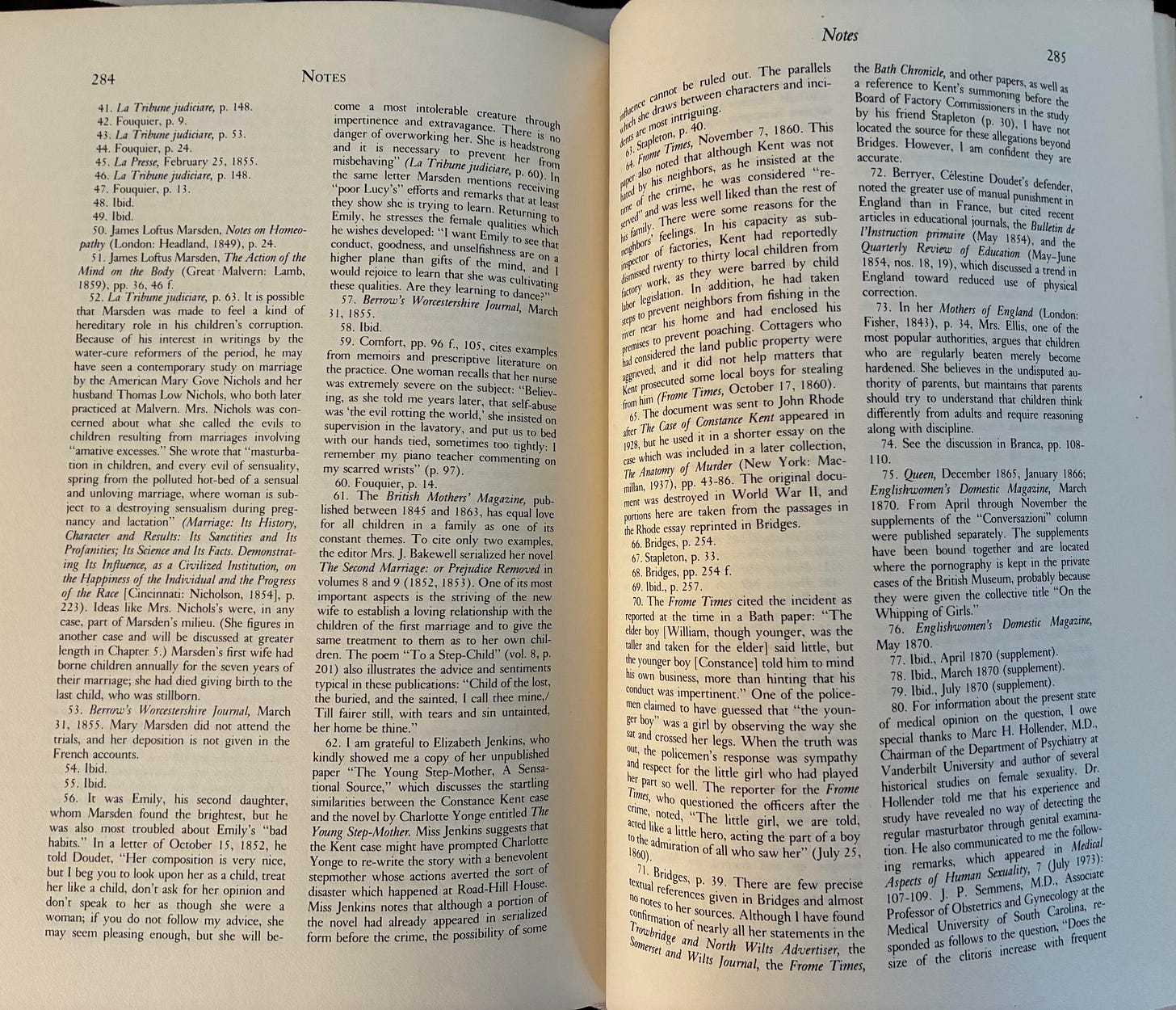

Some authors tuck lots of bonus information into their notes sections, as you can see here in this spread from Mary S. Hartman’s Victorian Murderesses, which has held a cherished place in my library for well over three decades.

I think that this sort of thing is fun as heck, and it gives you something amusing and semi-secret to read while you’re reveling in an author’s scholarship.

Superscript numbers, by the bye, not unlike footnote symbols rebirthing themselves page by page, resume at 1 with each new chapter; otherwise, with some books, you’d be looking at notes numbered into the thousands, which (a) is oppressive and (2) would look dreadful.

Now then, back to blind, or catchphrase, notes.

When I got started in publishing back in the early 1990s, nearly all the nonfiction books I worked on had, as shown above, numbered notes (the nonfiction books that included notes at all, that is; not all nonfiction books include notes). Tastes began to shift, though, as (some) authors decided that superscript numbers made their books look more academic than they, the authors, would like. The result of that taste shift is this:

But but but . . . There’s nothing there at all!

Precisely. Now turn to the back of the book.7

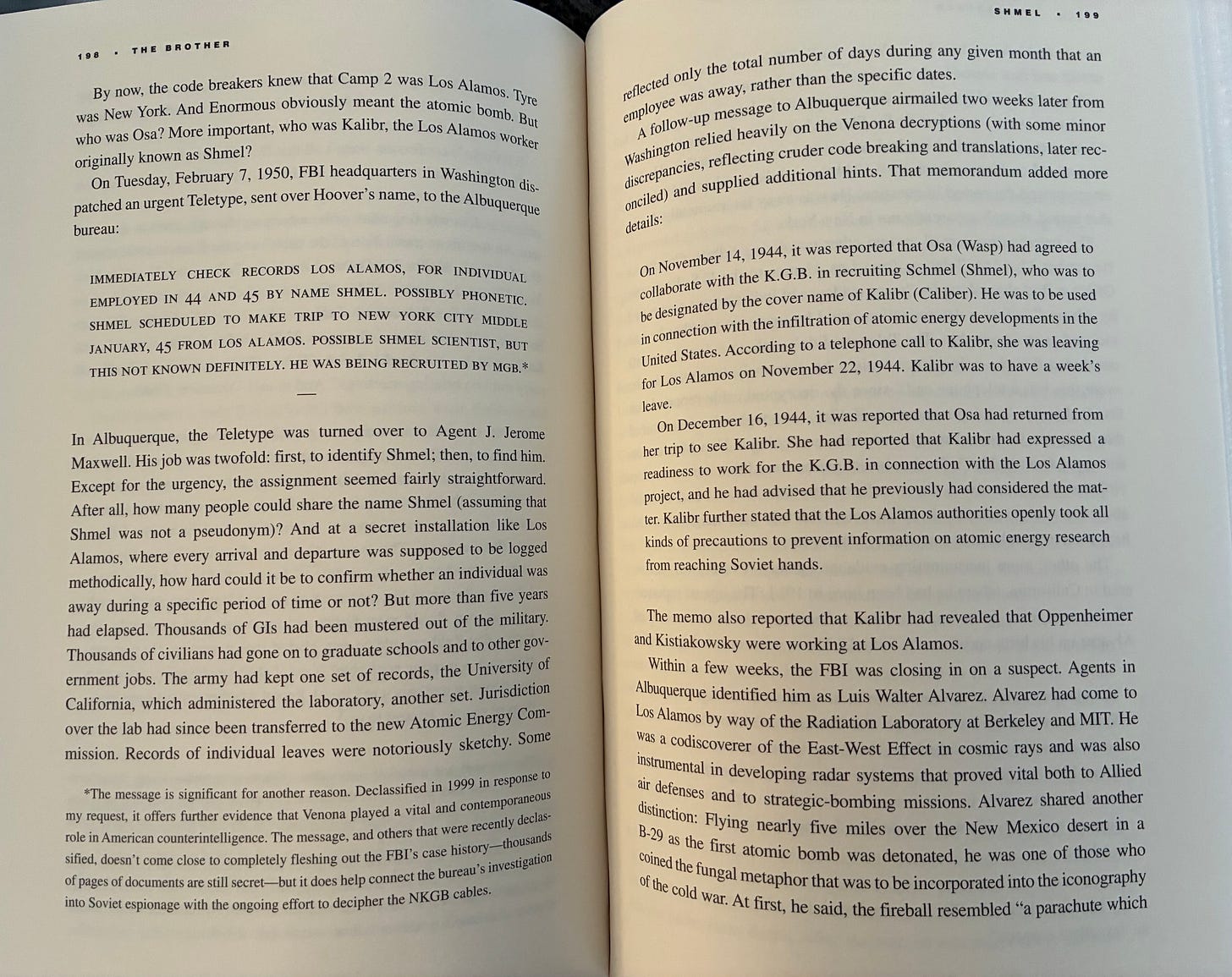

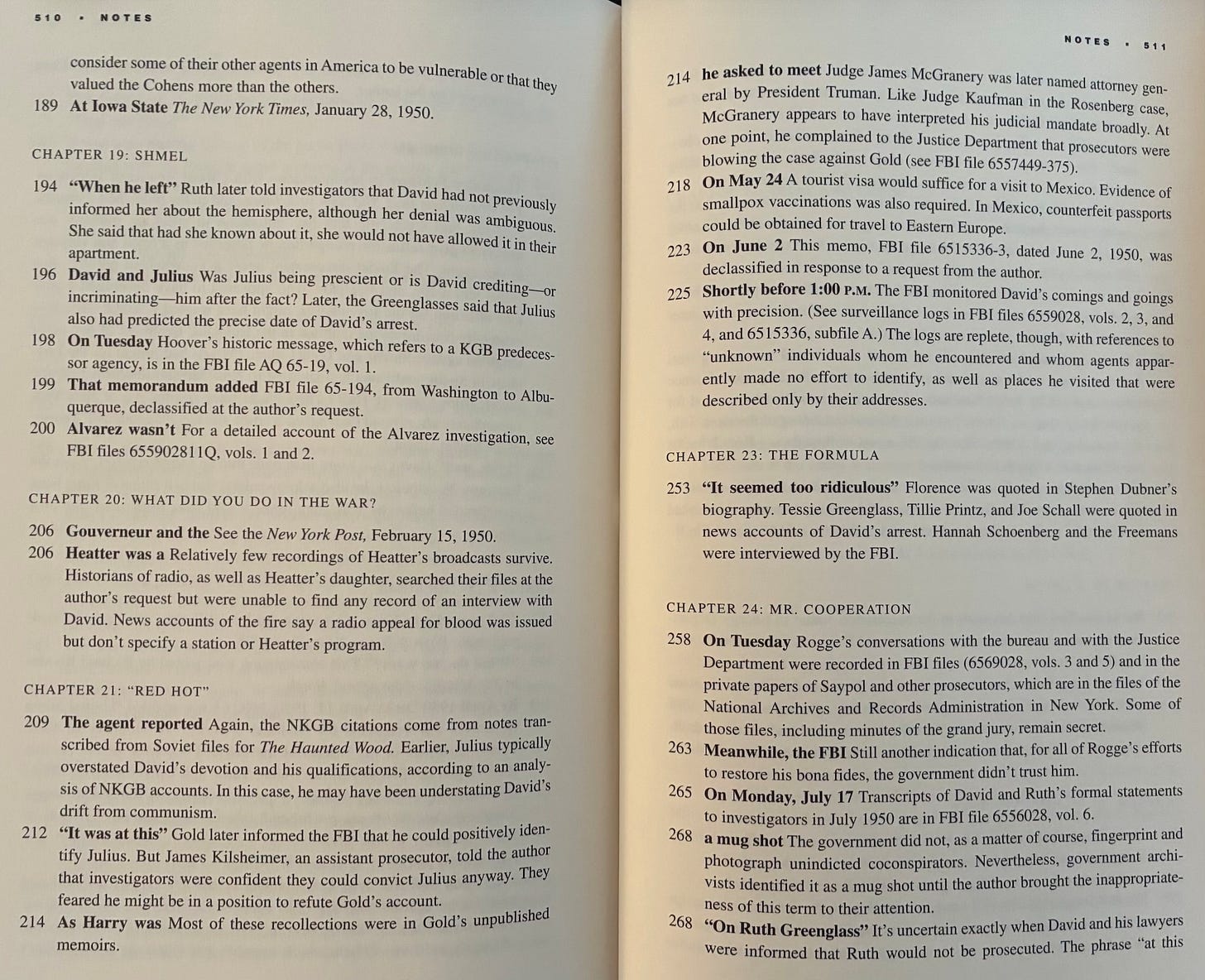

And thus we match up the note kicked off with 198 On Tuesday with the phrase “On Tuesday”8 on, indeed, p. 198, the note kicked off with 199 That memorandum added with the phrase “That memorandum added” on p. 199, etc.9 And thus as well the pages of the book proper are a bit less cluttered, a bit less academic/textbooky-looking.

By the time I retired in late 2023, I’d estimate that upwards of 90 percent of the nonfiction-books-with-notes we published at Random House included—by author preference, to be sure; we were accommodating in either direction—blind/catchphrase notes rather than numbered notes.10

Do you want to know where citational/bibliographic information—as in the Edison and Victorian Murderesses notes sections sampled above—doesn’t belong?

On the main text pages of a book.

And yet: Any number of academic and university presses seem to feel otherwise and, in making that feeling manifest, produce books that can charitably be described as absolutely unsightly,11 but chacun, as they say, à son goût.12 I’m sure that having bibliographic citations (especially those interminable URLs that run to two or three lines, who doesn’t love to see those?) hogging up half of each text page delights the folk who are cited in said citations, especially when they’re revving up to accuse the author of the book in hand of plagiarism, but for the rest of us: Stick that stuff where the sun don’t shine, back in the back, where it belongs.

And invest in a couple of bookmarks.

My ongoing gratitude to subscribers, with particular gratitude toward subscribers who have chosen to support this endeavor of mine financially with no greater reward (beyond my gratitude, that is) than being able to chitchat with me in the comments sections. I appreciate it more than I can say.

Sallie appreciates it as well.

Stay tuned, by the way, for my conversation, which I’ll be posting here on November 28, with the effervescent Elizabeth McCracken in honor of her forthcoming A Long Game: Notes on Writing Fiction, which is simply marvelous and which you should certainly consider preordering.

(Though I’ve got a missive in mind to publish here before the 28th rolls around, maybe two missives.)

And a gentle but eager reminder, for those of you who live in or frequent Los Angeles, that on Monday evening, December 15, I’ll be appearing with my friends Annabeth Gish and Kerry O’Malley in In the Night. In the Dark. A Shirley Jackson Evening. It’s going to be vast fun—chills and thrills guaranteed—and I hope I’ll see some of you there!

Cover image: Nicholas Kepros as Emperor Joseph II of Austria in the New York premiere of Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus (1980) (photograph by Martha Swope)

This entire piece, I should point out up front, concerns notes as they appear in print books. Back in my employed days I didn’t have much to do with the creation of our ebooks—I had a number of wizard colleagues who had a lot to do with the creation of our ebooks—but I’m reliably informed that the ebooks produced by Little Random (a persistent and I think endearing nickname for what is currently called the Random House Publishing Group dating back to the days when our group and our parent corporation were both named Random House) are, besides attractive, exceedingly user-friendly and easy to navigate.

Or, if you will, in the big room.

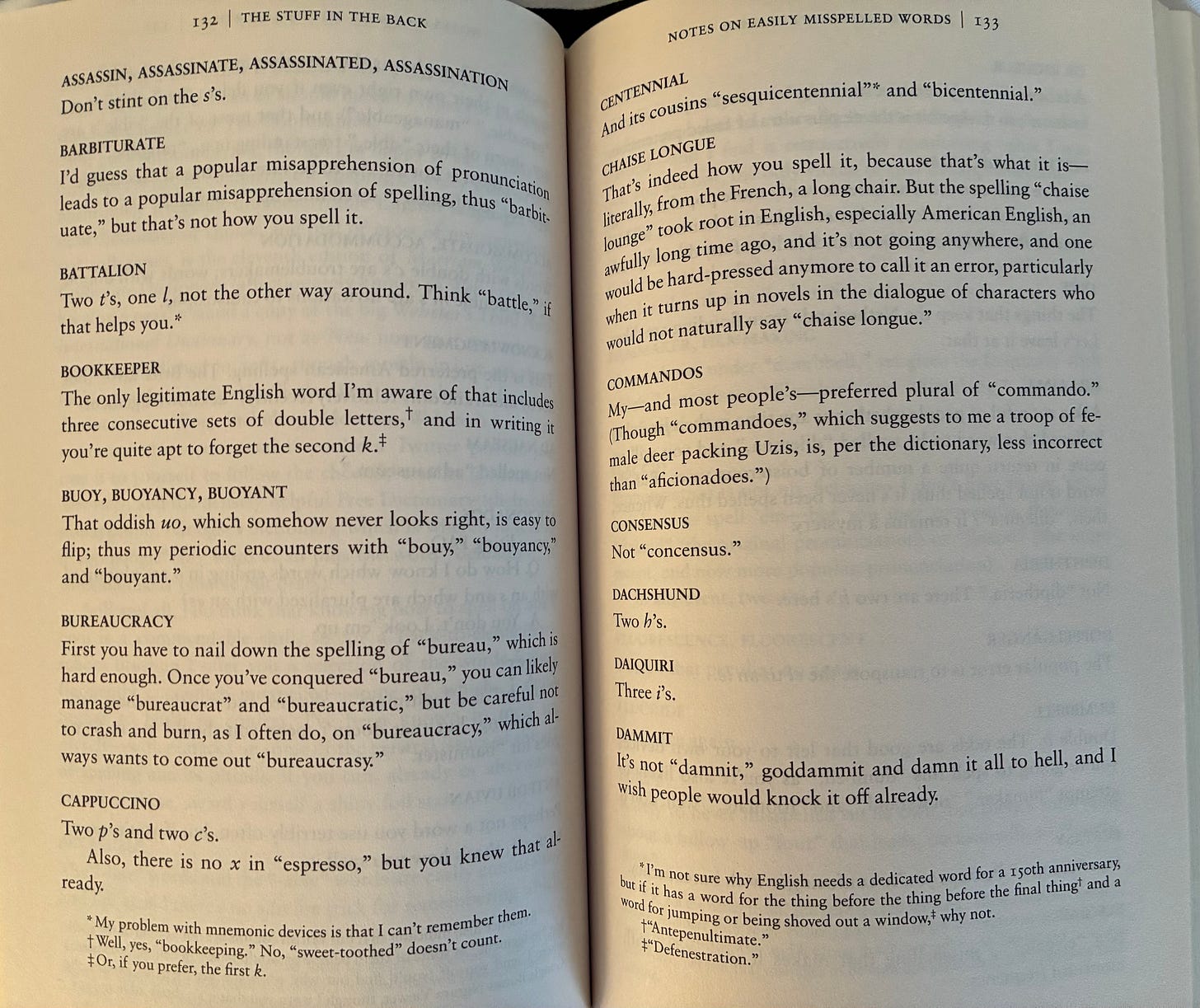

I’ve realized after the fact that I randomly selected the one page in Dreyer’s English (p. 133, that is) in which I dared to footnote a footnote, which was easy enough to execute in print but boy oh boy how the ebook folk hated my guts.

Even I’ve never managed to get six footnotes cooking on a single page. (I should take that as a personal self-challenge, I suppose.) But if you do whip up six footnotes and are on your way to a seventh, you’d then conjure up a double asterisk, and then, for an eighth, a double dagger—um, a double single dagger, that is—and then onward to a double double dagger, and OK really you need to stop now.

If a footnote’s text runs, of necessity, onto a second page, it’s often the done thing to precede the second page’s overflow footnote text with a horizontal rule.

Also, as you’ve by now already noticed, but I should point it out anyway (in case you thought I hadn’t noticed), we don’t do the footnote symbols thing here at Substack; we do numbers. Which, to be honest, works best in this format.

Speaking of saving pages, one reason I like to see bibliographies preceding notes sections is that the author can then load up their bibliography with full citational information for each cited work and then provide streamlined information in the notes section right off the bat.

What citational information should an author provide in bibliographies and notes, and in what format and style? Ah, that’s why you own a copy of the 18th edition of The Chicago Manual of Style. So you can look that stuff up.

Also: It’s an old-school bespoke nicety to set the running heads of the pages of a notes section to indicate what pages’ notes are included below (i.e., something like, up top, “Notes for pp. 187–89”), but it’s a nicety that’s largely gone by the wayside. I guess I miss its bespokeness and niceness.

The book in question is Sam Roberts’s The Brother: The Untold Story of Atomic Spy David Greenglass and How He Sent His Sister, Ethel Rosenberg, to the Electric Chair, and that’s sure a mouthful of subtitle, but when you think about it (and, trust me, we all thought about it a lot) it includes just as many words as are necessary and not, I’d say, a single word in excess, to let the bookstore browser know what the book is about.

And this is where I get to say that every single time I see a subtitle that commences “The Untold Story of,” I exclaim, “But it’s not untold! You just told it! It’s this whole book!”

My little joke.

One of my little jokes.

Sam’s catchphrases run, to be honest, a skosh short for my taste. I think that a catchphrase of four to six words is ideal for helping the reader match the text to the note and vicey versey.

The page numbers, to be sure, can’t be finalized until the book is nearly done. (Text gets added and cut over the course of the production process, spreads are adjusted to eliminate widows and bad breaks, etc., and so things keep moving around, a little or a lot.)

Oh, as long as we’re here: The manuscript would have simply included placeholding 000’s where the page numbers would eventually go, and so would the first set of typeset pages.

What one rarely sees any longer is what I think of as the chatty notes section, in which an author simply narrates/summarizes, chapter by chapter, where they got their stuff. Here’s an example (the Cukor bit alone is worth the price of admission) from Gavin Lambert’s biography of the actress Alla Nazimova (aunt, by the way, to my beloved Val Lewton).

I’m not providing samples because that would entail shaming the authors of such books, who may well not have had any say in the matter. (I couldn’t much care less about shaming the publishers.)

“Everyone has gout.”

Noted.

I love how how you've attributed the title quotation without, as far as I could see, actually mentioning it.