About a decade ago, I was in London for one of my periodic head-clearing jaunts and, on the day in particular question for this ’stack recollection, en route to lunch with my writer friend Ann Wroe, whose biography of Pontius Pilate, I would note, is one of the greatest works of nonfiction I ever worked on in my Random House career and one of the greatest works of nonfiction I’ve ever read in my life.

Here’s an early taste of it, which, given the book’s subject, you might find wonderfully bracing, perhaps even a little (in the best ways) disorienting.

On the seventeenth day of September 1870, a gale of extraordinary force swept ashore in Blackpool. By eight in the evening, it was impossible to walk along the beach. Men in stovepipe hats and newsboys in caps struggled, bent horizontal, across the sandflats. The tide ran fast with unaccustomed foam; toward Ireland, the night sky towered like a bruised fist.

All night the wind blew. Behind the Manchester Hotel, the sea destroyed the embankment of the Lytham and Blackpool railway. The rail bent and sagged over gaping air. In two places the waves crashed through the promenade, sweeping away field walls and pouring in a torrent across the Lytham Road. John Knowles, a local farmer, lost four fields of oats, reduced to a mass of blackened straw floating with the scum of the sea.

In the morning, bleary walkers found the water knee-deep inside the Blackpool gasworks. Bathing vans had been blown all over town, tipped on their sides in the middle of roads, or upended in fields far from the water’s edge. Their spars stuck up like the horns of giant cattle. Oddest of all was the fate of the wooden confectioner’s kiosk that had stood at the corner of the Foxhall Road. It was found upside down in the middle of the bowling green, as if challenging customers to exchange their woods for gobstoppers, jawbreakers and fizzing sherbet balls.

I’ll leave you to see for yourselves where this story is heading, and how and why.

In any event, I was, as I said, on my way to have lunch with my friend Ann and was passing through Cecil Court, a notably quaint (even for London) alleyway of bookshops, antiquarian dens, etc., just north of Trafalgar Square.

I stopped in, as I like to do, at Mark Sullivan Antiques, the sort of place you might visit if you were in the market for a venerable glass paperweight with an image of St. Paul’s in it, a tiny lead Mr. Bumble or Uriah Heep figurine, a Toby jug, or even a whist marker.

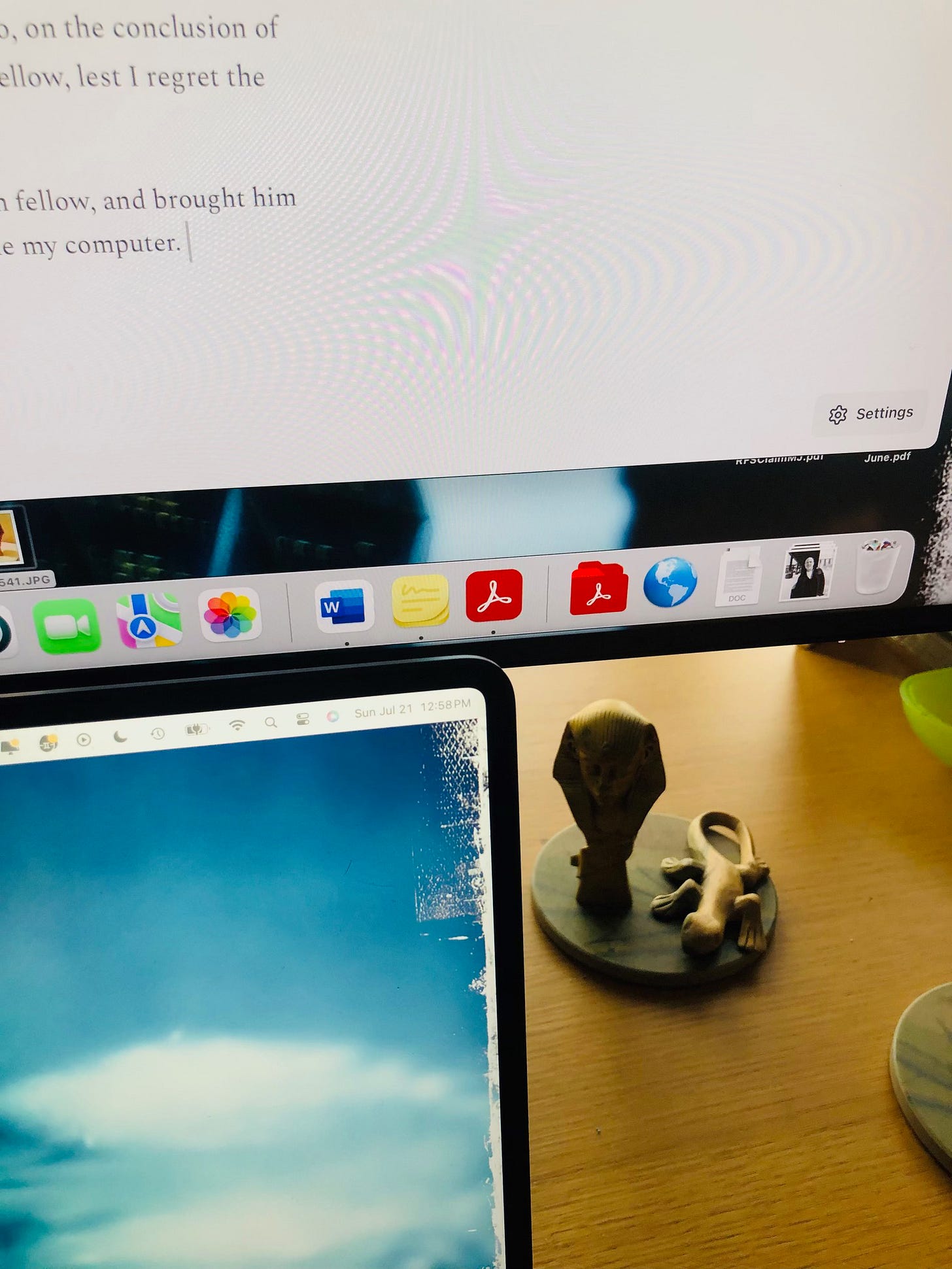

And then I saw this little fellow:

I was of course immediately besotted. Enchanted, even, perhaps literally. I mean, how could one not be.

He wasn’t terribly expensive, even, as old objets go, maybe 50 quid or so?

But I hesitated over the necessity of acquiring yet another little (he’s about four inches tall, by the bye) trinket in a long lifetime of little trinkets—heedless, I suppose, of the fact that the point of little trinkets is their lack of necessity.

So I made the de rigueur “I’m sure I’ll be back later” noises and proceeded to lunch, where, amid the tons of catching up Ann and I needed to do—

Oh, here’s a photo of Ann and me, taken a few years later on another head-clearing London jaunt:

—I told her about the little Egyptian fellow.

In her briskly, gently no-nonsense fashion, Ann ordered me to, on the conclusion of our lunch, return to Cecil Court and buy the little Egyptian fellow, lest I regret the nonpurchase for the rest of my life.

And so I returned to Cecil Court, bought the little Egyptian fellow, and brought him back to New York, where he’s resided ever since just beside my computer.

The truth, of course, is that if I hadn’t made the purchase, I’d likely have forgotten all about the little Egyptian fellow, but now I have both the little Egyptian fellow and the story that goes with him, so I think I’ve done quite well for my 50 quid or so.1

“Haunted,” a friend just commented, seeing a photo of my companion.

“I’m waiting for the day his eyes open,” I said.

“It will be the last thing you see,” she noted.

I recall (somehow both vaguely and with great certainty, in that way one has) that a few years ago I figured out whence the little fellow originally came by tracking his “Sommeil du Nil” branding (to an auction site, I think? perhaps he was an advertisement for a perfume?) and that I also found an image of a brother of his, except partly made of ivory. Curiously, I’m now entirely unable to retrace my steps.

No regrets. The eternal lie.

Driving wherever the road took us, we stopped in a shop in Baccarat one afternoon in the spring of 1984. Cufflinks like little flower-filled paperweights caught my attention, and I had a hard time deciding between red and blue. "You don't need both sets," my other half said. It's 40 years now. Mr. Bernstein has his girl from the ferry, with a white dress and parasol; I have the blue buttons I left behind. The last eight years have sharpened the regret.