Friends with Words

[a divertissement]

“Why,” an inquiring friend inquired yesterday, having completed the day’s New York Times Wordle puzzle, “is it spelled ‘fiery’ and not ‘firey’?”

What a good question!,1 I thought, having not an atom of an iota of a notion as to the correct answer.

“Middle English,” our friends at Merriam-Webster inform us: “from fire, fier, fire.”

An answer that comes exceedingly close to “Because we say so.”

A little further rustling around the etymology bush led me to this:

late 13c., “flaming, full of fire,” from Middle English fier “fire” (see fire (n.)) + -y (2). The spelling is a relic of one of the attempts to render Old English “y” in fyr in a changing system of vowel sounds. Other Middle English spellings include firi, furi, fuiri, vuiri, feri. From c. 1400 as “blazing red.” Of persons, from late 14c. Related: Fieriness. As adjectives Old English had fyrbære “fiery, fire-bearing;” fyren “of fire, fiery, on fire;” fyrenful; fyrhat “hot as fire.”

Which also comes exceedingly close to “Because we say so,” but it’s “Because we say so” with a lot of fancy backup, and thus I’m satisfied. (As was my inquiring friend.)

Meanwhile, the pangram over at the Times’s Spelling Bee day before yesterday was MALEFIC, which, truly, I might, having played it, gasped over. What a grand word (as is its cousin “baleful”), positively dripping with eldritch horror. Before I hopped over to M-W to ascertain its date of first use, I took a guess and landed, with peculiar specificity, on 1453. Do you want to take a guess for yourself? I’ll tuck the answer below, in a footnote.2

MALEFIC followed nicely from the word I’d Genius’d out with the day before the day before yesterday: WIGHT, another venerable relic with a huge and rich and creepy history, one that I’ll always associate with my first encounter with it, via the barrow-wights of The Lord of the Rings.

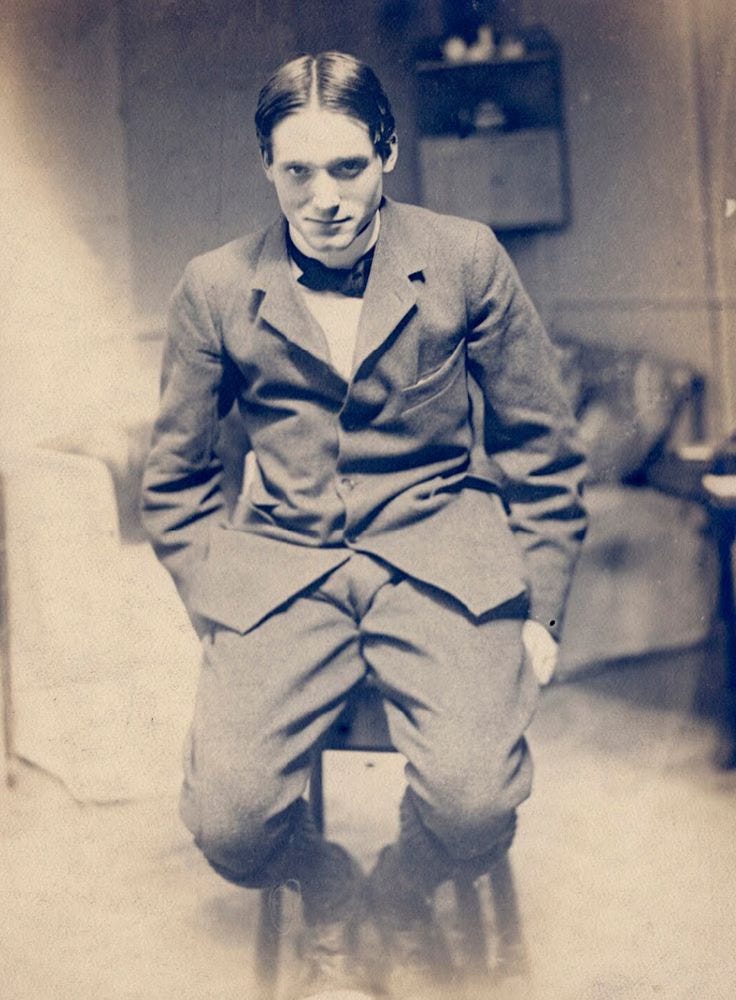

Also meanwhile, I’m continuing to read, with huge pleasure, Harley Granville-Barker’s The Voysey Inheritance, first produced in London in 1905 and one of the earliest plays I can think of whose playwright reproduces the hemming and hawing, the stopping and starting, of human utterance rather than simply arranging things in tidy, well-manicured speeches. For instance:

And I feel it my duty to—er—reprobate most strongly the—er—gusto with which you have been holding him up in memory to us . . . ten minutes after we have stood round his grave . . . as a monster of wickedness.

Perhaps this has something to do with HGB’s having started out as an actor.

More learnèd scholars of theatrical history than I may show up with earlier examples, and I’ll be happy to see ’em.3

In any event, I raise the subject of The Voysey Inheritance—which chronicles the exposure of a family’s legacy of financial malfeasance—particularly because it gave me a gift the other day of a word I’m reasonably certain I’d never before encountered in my life: “inspissated,” as in, and I quote, “the inspissated gloom of this assembly.” As a tot I recall being taught to attempt to suss4 out the meaning of an unknown word by reviewing its context, but as that technique wasn’t getting me far, or anywhere, with this one, I hied5 myself over to the dictionary to learn that it means

thickened in consistency

broadly : made or having become thick, heavy, or intense

Good word, eh? Perhaps let’s try to add it to our active vocabularies, I’m thinking.

Friends, as friends are wont to do, leapt in with a few other literary appearances, including, from Finnegans Wake:6

the shuddersome spectacle of this semidemented zany amid the inspissated grime of his glaucous den

and from Robert Graves’s Goodbye to All That:

Professor Edgeworth, of All Souls’, avoided conversational English, persistently using words and phrases that one expects to meet only in books. One evening, [T. E.] Lawrence returned from a visit to London, and Edgeworth met him at the gate. “Was it very caliginous in the metropolis?” “Somewhat caliginous, but not altogether inspissated,” Lawrence replied gravely.

Which is pretty dang funny.7

The other day I found myself reaching, with good cause, for the word “inferrable” and was taken aback to learn that “inferrable” is officially spelled not “inferrable” but “inferable.” (M-W also offers up, beyond the double-damning “variants or less commonly,” “inferible” and “inferrible,” which makes the absence there of “inferrable” feel to me like a personal attack.) A little nosing around online, I’m comforted to report, has disclosed that “inferrable” is scarcely unknown in printed English, particularly back in the early nineteenth century when things were a lot more Wild West wild than they are now.8

On one of my strolls earlier this week, I listened to the divine Michele Lee’s version of “I Believe in You” from the How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying soundtrack. In the 1967 film, “I Believe in You”—Bobby Morse’s climactic anthem of self-adoration in the original 1961 stage musical—is introduced early on, briefly, as a straightforward love song, and I would call such a preliminary use a “preprise,” a word I seem, alas, not to have coined but would be amused to see in wider use. (Another notable preprise is the introduction in the first act of the 2014 revisal9 of the musical Side Show of what had been in the original production the particularly thorny eleven o’clocker “I Will Never Leave You,” particularly thorny because the show is about the conjoined twins Daisy and Violet Hilton. In the revisal, the song is initially heard—again, relatively briefly—in the first act as the sisters’ expression of their terror of being surgically separated, and this, when the song then showed up again at the finale, went, I thought, a long way toward snapping shut the pockets of barely repressed snickering and nearly audible eye rolling that had greeted it, the night I attended, in its original 1997 production.)

Fiery.

Malefic.

Wight.

Inspissated.

Suss.

Inferable.

Preprise.

Revisal.

Make them yours!

(Perhaps not all at once.)

Thank you all for being here, and I express, as always, my particular gratitude toward subscribers and, particularly particularly, paying subscribers, with whose support I feel very much buoyed in a floundering or even foundering world.

Sallie is grateful as well, though she’s had it up to here and then some with the relentless local paparazzi.

P.S., just for a little Sunday fun for those of you who like theatrical trivia questions and haven’t already been on the receiving end of this one:

Name the actress who originated a leading role in a stage musical whose score included a song celebrating the actress’s real-life sister. (And name the show, and name the song.)

Ten A Word About . . . points to the first correct answerer.

Till next time,

B

I’m one of the only people I know to do that !, (or ?,) thing, and I’ve been known as well to contribute it to other writers’ writing when I’m copyediting them. It’s one of my few copyeditorial tells.

It dates to 1652. So I was close. Ish.

Post-publication I’ve been darting around the archives and refreshing my memory re earlier works like T. W. Robertson’s Caste (1867) and Arthur Wing Pinero’s The Second Mrs. Tanqueray (1893), and they’re both certainly John the Baptist–ing Granville-Barker’s naturalism; I don’t think they’re quite there yet.

It’s “chiefly British,” yes, I know, but I like it. As, I suppose, is the verb “twig,” which I will not try to get away with now or in the foreseeable future.

A word one can’t play at the 🐝, I note.

I haven’t had a practical opportunity in aeons to warn you that there’s no apostrophe in the title Finnegans Wake (or, for that matter, in Howards End), so consider yourselves warned anew.

Also, killing off one of your main characters—who the audience quite probably thought was your protagonist—between acts without so much as a by-your-leave is truly a baller move. Good job, Harley.

Two particularly witty friends provided, as alternate definitions to the word, however in the heck you spell it, variations on “not able to be turned into iron.” Which is one of the reasons one surrounds oneself, given the chance, with witty friends.

The word “revisal” has been knocking around for centuries, but it’s recently gained a particularly useful use in the theater to refer to (usually) musicals that have been, in the words of the writer Michael Schulman, “gutted and refurbished . . . to render them more palatable,” often by heavily rewriting their scripts (to the point of outright overhauling their plots), dropping songs and/or borrowing others from the original creators’ other works, etc. Though some revisals have notoriously, naming no names, taken competent or at least passably competent musicals and turned them into incoherent trash, the Side Show revisal, I’d say, having seen both Broadway productions of the show (and, I note, revised by its own creators, not by johnnies-come-lately), took something that had not, at least not from where I was sitting, worked hardly at all, solved approximately 79 percent of its problems, and made something harrowing and truthful where previously there’d been mostly overcompensating glitz. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, the revisal failed even harder and faster than the original version.

June Havoc on original Pal Joey (for which we had the original “album” on 78s growing up). Hia, Sallie!

This is my own story, as posted for my Facebook friends, of that particular Spelling Bee: The word "malefic" entered the English language in [dates redacted] to describe something producing disaster or evil. In 2026, not knowing that old word was the reason I didn't get the pangram yesterday in the NYT Spelling Bee, even though it actually dawned on me when I was playing it that the letters were just short an "n" and a "t" to make Maleficent, the evil being from Disney's 1959 "Sleeping Beauty." I was so close to getting it.