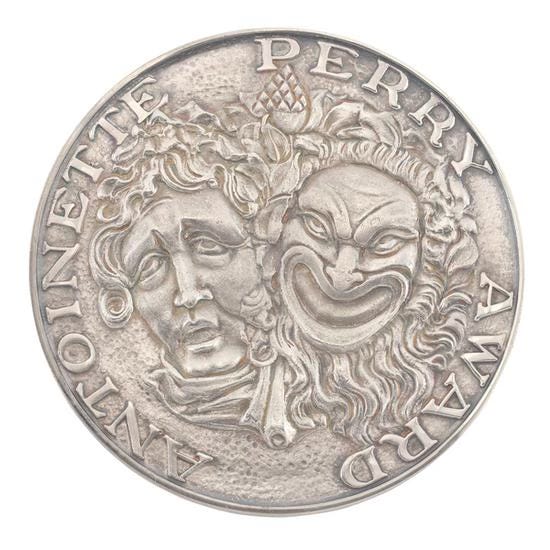

In the aftermath of this past weekend’s Tony Awards telecast, I participated in a brief—and, given the penchant of any online chitchat lately, or ever, to devolve into fisticuffs, genial—discussion of the thing itself. That is, this thing:

What—a plain enough question—do you call it, thing qua thing?

You could, I suppose, simply call it an award, merging the honor and the objet, but that doesn’t feel right to me.

Or you could call it a trophy, though that comes through as a bit too sporty for the theater, and one thinks, or at least I think, of attenuated cups with handles.

The highly detailed Tony Awards Rules and Regulations refer, in lawyerese, to the “Tony Award statuette (the ‘Statuette’), which incorporates an engraved replica of the Tony Award Medallion,” and, though, sure, the bemasked disc (the Tony folk spell it “disk,” a spelling I haven’t used for anything in years) is certainly a medallion,1 applying the word “statuette” to the entire contraption—the medallion,2 the base (or, if you like, the pedestal), the armature (or, if you like, the swivel)—isn’t, as mots justes go, quite juste to me.

A statuette, after all, is “a [small] three-dimensional representation usually of a person, animal, or mythical being that is produced by sculpturing, modeling, or casting,” and the distinguished Tonys tchotchke doesn’t, I’d say, meet the terms for statuettery, as Oscars and Grammys and even Sarah Siddons Awards do.3

So what—a not so plain enough question, I guess—do you call it, thing qua thing?

As tempted as I am to call it like it indeed is and refer to it as a Mounted Spinning Medallion, perhaps let’s draw a veil of discretion over the subject for another year and call it . . .

. . . a Tony.

Speaking of the theater and of mots justes, I was listening to My Fair Lady yesterday (the 1959 London cast recording I grew up with—because stereo!; one of my more pointless superpowers is being able to distinguish, within seconds, track by track, between the London version and the original 1956 Broadway mono version) and tripped galumphingly, not for the first time, over Alan Jay Lerner’s lyric, in “You Did It,” as Pickering describes Eliza’s triumph at the Embassy Ball:

They thought she was ecstatic

And so damned aristocratic.

Well, no, I thought peevishly (my regular state lately). She may have been ecstatic; surely the assembled swells thought she was . . . electrifying?

Of all the Golden Age musical theater lyricists, Lerner is, I’ve observed any number of times, the one who most frequently goes off the syntactical rails. Aficionados like to twit his putting the word “hung” into Henry Higgins’s mouth when the word “hanged” is called for (Higgins is, after all, an “expert dialectician and grammarian”), and “I’d be equally as willing for a dentist to be drilling / Than to ever let a woman in my life” is especially and multiply vexatious.

Lerner is also occasionally guilty of the kind of pronoun pileup and misdirection I’ve been trying to copyedit out of manuscripts for decades, for instance, from Camelot’s “Guenevere”:

I’ll wager the king himself is hoping he will return.

Why would he have chosen five a.m. for the queen to burn?

(The first “he” is Lancelot, the second “he” is Arthur, and it’s always a bad idea to apply the same pronoun to more than one person in a single thought. Also, I think we’re missing an “else” between “Why” and “would,” no?)

And it’s thanks to Alan Jay Lerner (perhaps this is the source of my bitterness) that I spent many years assuming that “gloaming” is not, as I eventually learned, a charming word for “the low light that is seen in the evening as the sun sets” but a kind of valley or hollow or meadow via, from Brigadoon, “The mist of May is in the gloamin’, and all the clouds are holdin’ still.” And you’ll never persuade me that Lerner didn’t somehow think that a gloaming, or even a gloamin’, is a kind of valley or hollow or meadow too.4

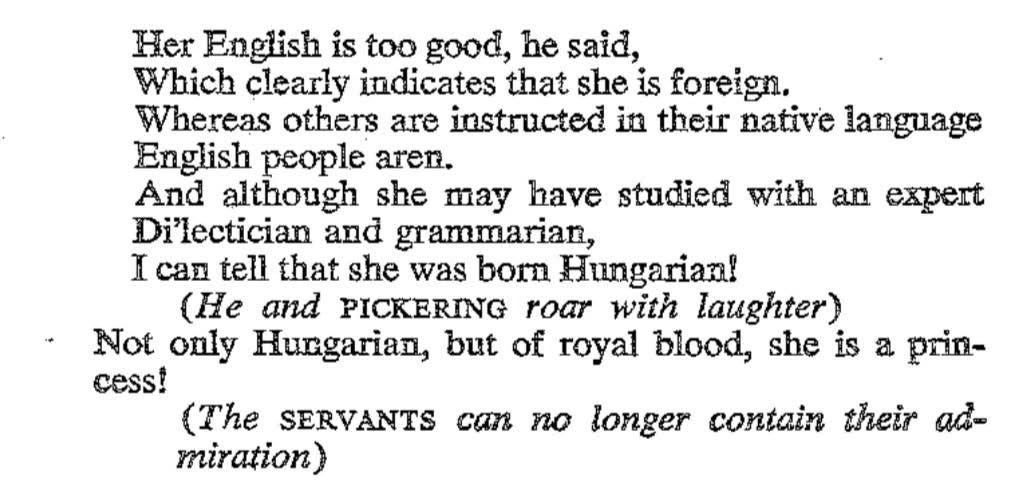

On the other hand, credit where it’s due, one of my favorite rhymes in all of musical theater, and we’re back to My Fair Lady’s “You Did It,” comes in Higgins’s recounting of his encounter with his former student the thickly accented “dreadful Hungarian” Zoltan Karpathy:

Her English is too good, he said,

Which clearly indicates that she is foreign.

Whereas others are instructed in their native language

English people aren’.5

It makes me laugh. Every time.

Bonus semi-relevant photograph: distinguished Dolly!s Pearl Bailey and Carol Channing at the 1968 Tony Awards

Thank you for dropping by, with particular gratitude to subscribers and, especially, those subscribers who support this endeavor financially. That you don’t have to do so, and do so anyway, means the world to me.

Sallie is grateful too.

Also, do, if you’re so inclined, hop over to my website and check out the merch, plus information on how to purchase signed copies of Dreyer’s English.

P.S. Designed in 1949 by Herman Rosse, who among his many achievements (I have just now learned this, and I’m excited to share the information with you) designed the sets for the 1931 film of Frankenstein, the medallion was originally presented to honorees on its own; the base/pedestal and armature/swivel were brought on in 1967.

In one of those charming, or at least weird, life-imitates-arts occurrences, the Sarah Siddons Award, presented annually by Chicago’s Sarah Siddons Society, was inspired by the fictional Sarah Siddons Award for Distinguished Achievement depicted in the 1950 film All About Eve (as was the Society itself), whose writer/director, Joseph Mankiewicz, eventually observed, “I invented it to put down all this fatuous prize-giving, and now there’s some outfit in Chicago actually promoting a Sarah Siddons Award every year, and people like Helen Hayes go out there and make tearful acceptance speeches.”

Yes, of course I could have, at any point, looked it up. But why would you look up a word whose meaning you’re sure (or at least sure-ish) of?

I don’t have the official lyrics in front of me (I’m sure that one of my scholarly friends will drop by to offer enlightenment as soon as I post this, at which point I’ll amend this footnote as necessary), so I can’t be 100 percent certain that Lerner wrote “aren’” rather than “aren’t,” but I’m certainly hearing “aren’” on the four recordings I have handy. We’ll see.

And indeed, post-publication update, mere seconds later (thank you, Kevin Daly!): Lerner wrote, at least as it was rendered in the published libretto, “aren” (no apostrophe).

Noting as well that though Lerner gives us, clearly, “Which clearly indicates,” Rex Harrison, in both New York and London, gives us “That clearly indicates.” Actors, what can you do with them.

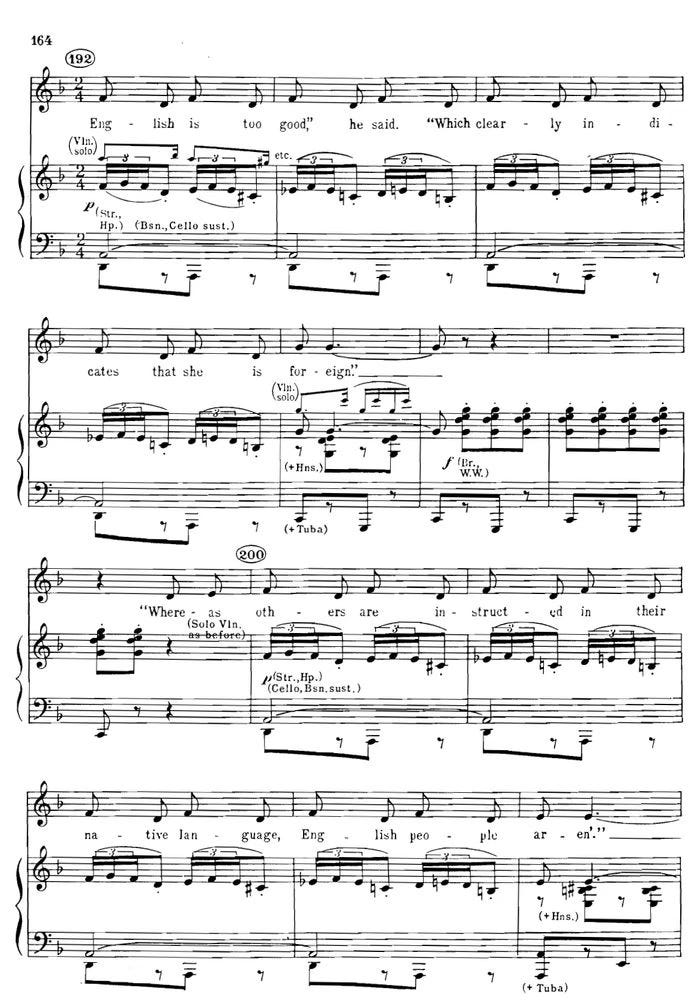

And here’s the relevant passage from the score (thank you, John Baxindine!), with apostrophe!:

P.P.S. Riffling through the libretto, I’ve also just confirmed that Sexy Rexy miscorrected AJL’s quite correct “If I were a woman who’d been to a ball” to an un-Higgins-like “If I was” etc., on both recordings!

I am one of four children produced by post-WWII parents whose only self-indulgence was their annual seasons tickets to the San Francisco Civic Light Opera. Not only did they use every ticket every season, but they purchased the cast album of each production, thus ensuring that all of their children would grow up knowing the lyrics of every song in every musical, however obscure. Couple that with the fact that our mother was worthy of the title "grammarian" in her own right, and quite an enforcer in her day, today's "A Word About . . ." essay has been the highlight of my otherwise dreary day.

I was amused to learn, relatively recently, that the Screen Actors Guild award is called The Actor. So at the SAG awards event an actor may give The Actor to an actor.