Diary of a Mad Copy Editor (part 2)

[on the care and feeding of writers]

So we were discussing—or at least I was—the process of getting to know a manuscript a reasonable bit before laying one’s glommy paws on it, and I do want to emphasize and reemphasize1 that listening to what a writer is up to before setting out to improve what a writer is up to goes a long way toward making one not only a better copy editor but the sort of copy editor that writers clamor to work with more than once.2

(Before I forget, and because not everyone, I was recently reminded, knows this: If you hover over or click on these pieces’ superscript numbers—hover over or click, that is, dictated by where and how you’re reading the text—the myriad footnotes will automatically present themselves to you. You needn’t violently scroll down and up, down and up. I wouldn’t do that to you.)

Now that we’re ready to get to work in earnest, here are a few pointers on how to combine cheerful authoritativeness and respectful deference in the service of, as I say a lot, helping to make a manuscript into the best possible version of itself that it can be—while3 always bearing in mind, between the writer and the copy editor, which is the dog4 and which is the tail.5

It’s OK to Not

Copy editors can feel self-compelled, even -compulsed,6 to visibly prove their worth by overfussing with text, and it’s hard sometimes to persuade oneself that an entire paragraph (or even an entire page!) can be allowed to live its life precisely as the writer wrote it without the benefit of one’s copyeditorial grindings of pepper and other seasonings-to-taste.7

“A village explainer. Excellent if you were a village, but if you were not, not.”

—Gertrude Stein, on the subject of Ezra Pound

It’s also perfectly OK to not explain8 every little thing you’re doing. I know it’s hard to believe, but writers are often smarter than you might think and know their way, at least a bit, around the English language. If you’re correcting a spelling error, you needn’t cite AU: PER M-W in the margin.9 If you’re making a style choice about, say, how to present the names of musical compositions, it’s not important to write (indeed, it’s important not to write) CMOS 8.195 in the margin, (a) because the writer, as smart as they are, might not know (or care) that CMOS means Chicago Manual Of Style, and (b) because the writer really doesn’t need to be schoolmarmed at.10 Do what needs to be done, and do it as reasonably quietly as possible.

If you do feel the need to explain a change, and sometimes it’s advisable to do so, do so as succinctly as possible. In the ancient paper days, when one was trying to conserve real estate in the margins, one might note AU: AWK or AU: REDUND in support/justification of a repair to address a bit of text that was indeed AWK[ward] or REDUND[ant],11 and AU: DANGLER12 was usually enough to justify some minor surgery on what is more formally known as a dangling participle or a dangling (or misattached) modifier but that everyone pretty much indeed calls a DANGLER.13

Beyond that, just be tactful. You can get away with, indeed, AWK. You can even get away with CLICHÉ.14 The sauciest one can allow oneself to get, I’d say, is to cross out a piece of particularly needless exposition (or, worse, a repetition of exposition that’s been offered once or twice already) and note in the margin:

AU: We know.

🫢.

My Favorite Stealth Change

Always apply the series comma15 (unless one has been forbidden in advance to do so by one’s employer, which quite possibly means that one is employed by a newspaper, a magazine, or a Brit). Don’t ask. Don’t offer up a single “AU: OK?” in the margin. Just add the bloody comma, each and every time you can.

In the next installment of Diary of a Mad Copy Editor (and I note this here in part to help me remember):

• how to get an author to do what you want (and make them think they thought of it)

• when it’s OK to offer an author a bit of praise (spoiler alert: occasionally, by which I mean rarely), plus the celebrated smiley face story

• and much, much more16

Cover painting: Robert Braithwaite Martineau (1826–69), Kit’s Writing Lesson (1852) (oil on canvas, 52.1 x 70.5 cm, The Tate Gallery)

Thank you for being here, with particular thanks to subscribers and extra particular thanks to those of you who not only subscribe but pay to do so.17 I’m well aware that there’s a lot of writing out there, and so many places to spend discretionary income, if one is fortunate and privileged enough to have any,18 so the fact that you’ve decided to support this endeavor of mine financially means a lot to me. Paying subscribers do get to comment on these missives of mine, and ask relevant (or at least semi-relevant) questions, and I’ll always do my best to respond.

Sallie is grateful as well, if a bit sleepy after a vigorous early-morning session of playing catch on the beach.

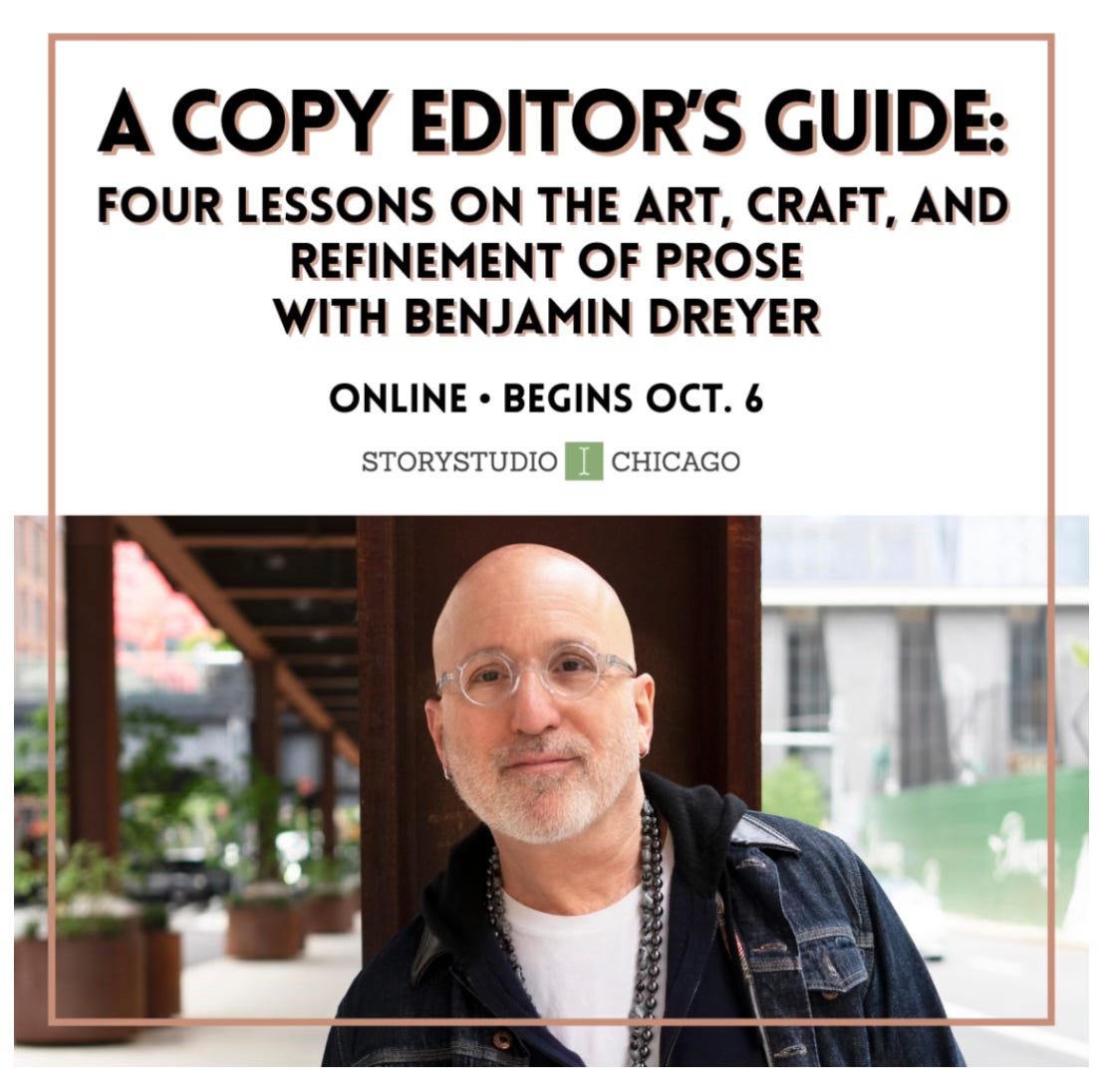

And just a reminder that in a few weeks I’ll be commencing a four-part online copyediting course for the excellent StoryStudio Chicago, and perhaps I’ll see you there!19

Or reëmphasize, if you’re The New Yorker.

In my copy chief days, I always strove to broker and maintain a happy marriage between a production editor—the in-house staffer who oversees the copyediting and proofreading of a book, plus its sundry appurtenances like the jacket/cover, the index, etc.—and an author over the course of multiple books, because familiarity over time smooths the process for everyone. The same then goes for matching up the freelance copy editor and the author, especially for novelists who write series. But in any event, there’s no greater compliment to a copy editor and their work than that an author wants to work with the copy editor again.

“Whilst” is for Brits. Also I’m beginning to sense that I’m aiming to set a footnotes record today.

Not you.

Hello.

I’m advised by the red dots of shame, to say nothing of multiple dictionaries, that “compulsed” isn’t a word. Well, it is now.

Please take “this can be a hard lesson to learn” as a given for this point and all subsequent points. No copy editor starts out perfect, and the temptation to show off one’s erudition is the mark of a novice. Trust me, I can still tote up my heavy-handed, wet-behind-the-ears sins, decades later.

Q. So it’s OK to split an infinitive?

A. Yup.

AU, to be sure, is “author,” and in the old days of applying pencil to paper, one made sure to make sure that the author knew that they particularly were being addressed, because one might also be directing the occasional comment/correction/guidance at the COMP (for “compositor,” i.e., if one were still living in the era of actual typesetting, which one probably wasn’t, the typesetter). M-W is Merriam-Webster, by unspoken consensus the dictionary of choice of the American book publishing industry.

As well, copy editors provide stylesheets—possibly of interest to the writer, absolutely of interest to the proofreaders who will be working on the text down the pike—indicating what resources they used in styling and dressing up a manuscript, and a stylesheet is a perfectly good place to give a shoutout to one’s dictionary and style manual(s) (plus, usually, provide commentary on punctuation and grammar, lists of proper nouns, and an A-to-Z guide to noteworthy and/or eccentric spellings).

To cite one of my favorites—favorite because I nearly overlooked it the first time I ran into it, and what’s more fun than elusive prey?—“social faux pas.”

“Driving along the highway, the weather was fine.” That sort of thing.

One no longer, in the e-copyediting era, needs to be quite so telegraphic in one’s copyeditorial chitchat, but resist the temptation, if one is tempted, to drone at an author. Least said, soonest mended, and all that.

Oh, a story!

Once upon a time—we’re back again in my copy chief days—one of the production editors in my department came to me in a considerable state of consternation, because an author, in reviewing their copyedited manuscript, had stetted the freelance copy editor’s graceful correction of easily a dozen and a half danglers over the course of the manuscript—as I recall, the first one was in the very first sentence of the novel, perhaps the second. And though, to be sure, ultimately an author is indeed the author of their own book—that’s why we call ’em authors—one’s job is occasionally to protect an author from themself whether they like it or not (and, not entirely coincidentally, to protect the reputation of the house—no one wants to read a review calling out a book for being poorly edited and/or proofread). The production editor and I duly marched over to the book’s editor’s office and explained what was going on. “I’ll take care of this,” the editor said. The next day, and presumably one tactful if stern phone call later, we were instructed to proceed with the dangler repairs.

Though one might want to go with CLICHÉ? It’ll make the writer feel a skosh less pointed at.

(Did you know that the pointy finger type mark—roughly 👉🏻, in emojese—is called a manicule? Back in the days when I kept handy, solely, or nearly solely, for my own amusement, a collection of rubber stamps, the manicule was always my favorite.)

AKA the serial or Oxford comma.

Meaning things I haven’t thought of yet, but will.

Did you note that this is the second not-only-X-but-Y construction in this piece? I sure did. I leave it here as a reminder that writers love not-only-X-but-Y constructions, and if they commit one, they’ll commit a dozen. It’s a thing to be mindful of.

Also, some writers favor the construction not-only-X-but-also-Y; I tend to think that the also is de trop.

Especially these days.

I know that everyone always signs up for these sorts of things at the last second, but think how cool you’ll feel if you take care of this sooner rather than later!

My favorite copy editor moment: when I was writing about the central joke in Guys and Dolls I said something like "the men have all the power, but the women always win in the end." The copy editor, who was a woman, as it turned out, wrote in the margin, "that's because the women have all the brains. Even Adelaide." I put it in the next draft, she said she didn't mean for me to use it, she was just trying to amuse me. But what a good catch.

I can't wait for:

• how to get an author to do what you want (and make them think they thought of it)

Pencil sharpened.