In a long-overdue burst of organization and other housekeeping, I’ve been, these last few days, going through boxes and folders full of the paper and paperwork that tend to accumulate over the years when one forgets—or at least when I forget—to occasionally sort through things and, more important, throw things out.

I’ve been doing this work especially painstakingly because, my organizational skills being what they are, ancient bank statements and yellowed receipts and how-to manuals for TV remotes I haven’t owned in a decade are often mixed in with personal correspondence, and I don’t want to blindly, thoughtlessly dispose of anything meaningful.

Happily, my care and patience have led me to locate something I knew was around here somewhere, but who even knew where, and I thought you might like to see it.

And of course: There’s a story first.

When I moved to New York from Chicago in the late 1980s, I sought out the sort of employment I’d already been doing for more than a decade and applied for waitstaff work at two posh-looking spots within easy walking distance of my apartment (like, fall-out-of-the-living-room-window easy). Both restaurants offered me jobs, and things being—or at least seeming—equal, I chose to take the job that came with the prettier dining room: huge columns, soaring ceilings, a slim balcony of tables overlooking the main floor (we tried hard to pretend that it wasn’t, in restaurant parlance, Siberia, but it was, and no one ever wanted to sit up there unless they were hiding from someone), and a sweet little raised cocktail area overlooking, through great big plate glass windows, lower Fifth Avenue. As it happened, this charming-looking restaurant wasn’t built to last, and not too many months passed before it was shutting down and my career in restaurants was shutting down with it.1 Which is how, by a roundabout route thereafter, I found myself in the freelance proofreading/copyeditorial business and, eventually, on staff at Random House, and the rest is (a) another story entirely, and (b) (personal) history.

I do, though, think sometimes about how if I’d taken the job in the other place, which is still going strong,2 I might well have remained in the restaurant business, risen through the managerial ranks, and, who knows, perhaps eventually opened a chic farm-to-table artisanal hotspot of my own in some piquantly raffish section of Brooklyn.3

Anyway, decades later I’m certainly glad I finally flunked out of restaurants—or got flunked out of them, really—because here we are, you and I.

Anyway anyway, during this last service stint of mine, I regularly attended to, among others, a lot of the publishing folk whose offices were nearby,4 including one Jonathan Dodd, a scion of the venerable (what other word can I use for a publishing house whose history went back to the mid-nineteenth century?) Dodd, Mead & Co., a lovely chap who always took his solo lunch at the bar5 and always had a good story to tell. (I was mostly hosting by then, so I had plenty of time to kibitz once the rush died down.)

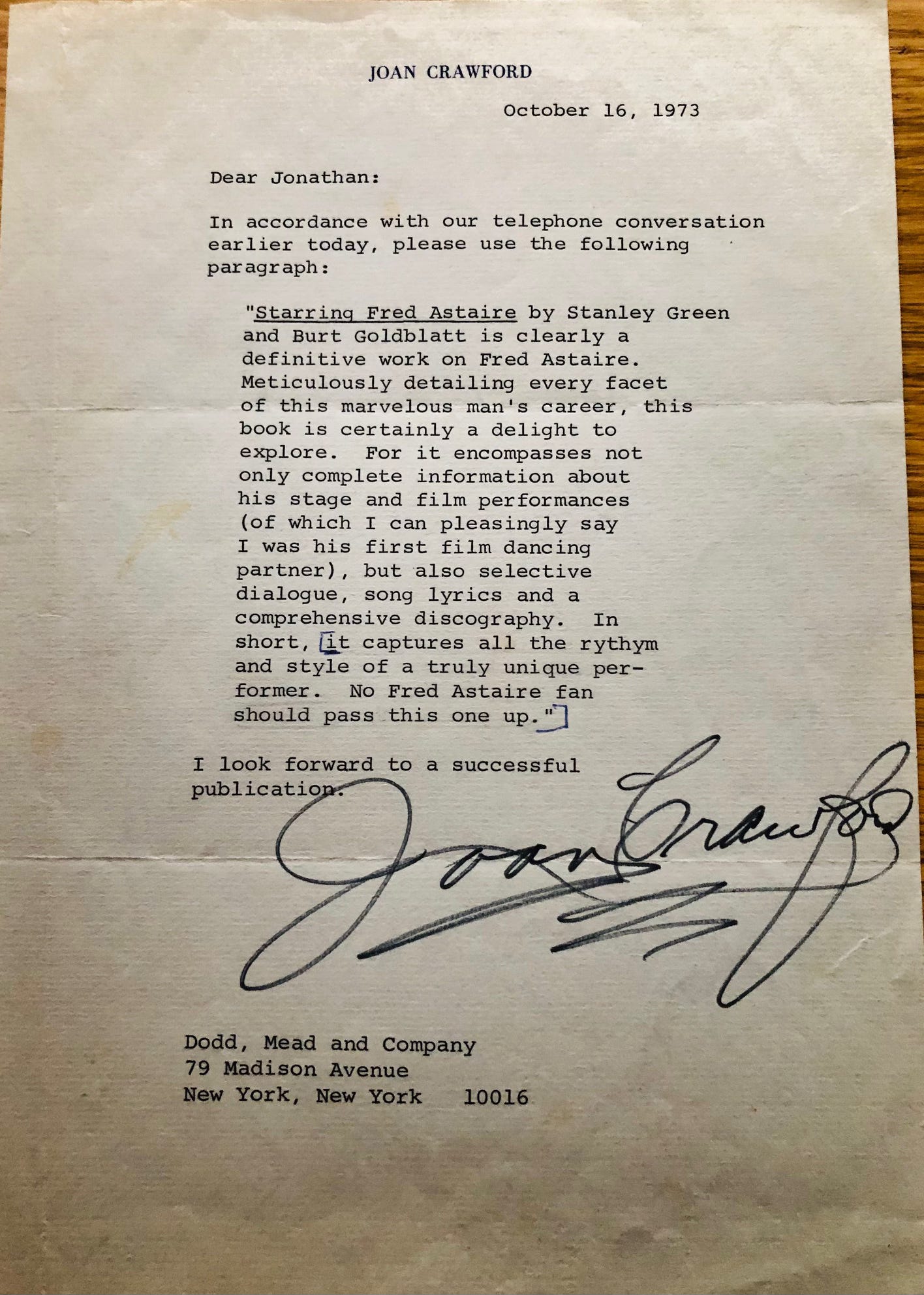

Eventually, Jonathan decided to retire, and one afternoon after he’d been—apparently, like me this week—sorting through boxes and folders of paper and paperwork, he gave me a little gift, herewith shown:

And of course: There’s more story.

Jonathan had solicited—by letter, of course—endorsements for this Starring Fred Astaire book from people who’d worked with star Fred Astaire, a group that indeed included Joan Crawford, the star of Astaire’s first film, 1933’s Dancing Lady, and, as she pleasingly notes, “his first film dancing partner.” (Fred played himself, and it was a supporting role; Joan’s actual costar was dashing Clark Gable.)

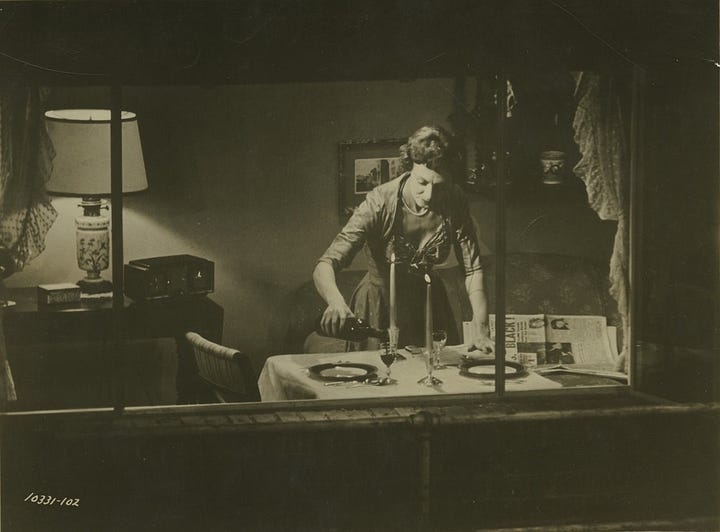

Here, for your amusement, are Joan and Fred in the “Let’s Go Bavarian”6 number:

Meanwhile, back in the early 1970s, there was Jonathan in his office one day, and his secretary buzzes him to say those improbable and magical words “Jonathan, Joan Crawford is on the line,” and Joan Crawford was indeed on the line, eager to dictate to Jonathan her crisp paragraph of praise.

I presume that Jonathan was listening but not in fact playing stenographer, because he did, as he told me, request of Miss Crawford, just to keep things official and tidy and legal (and, really, when someone phones you and claims to be Joan Crawford, who knows who they might be?), that she have her gracious encomium typed up and forwarded by mail.

Which she duly did, as you can see. Did Joan Crawford do her own typing? I like to think so, and the misspelled “rythym” lends credence to my thought. (Hey, it’s a hard word to get right. You know that as well as I.)

I also recall that when I was given this letter, well over thirty years ago, it was a pale lavender. Things fade over time, I hear.

Oh, here are two additional—and charming—photos of Fred and Joan through the ages.

I find all this digging through the past both dust-raising and emotionally taxing, as I relive my life letter by letter (not so much bill by bill and statement by statement; I mostly prefer not to think about how much money I once spent on lord knows what), and I’ve wandered over to my desk in the aftermath of today’s cull to soothe my jangled nerves with a bit of writing.

If you’d suggested to me five years ago that I’d ever seek to self-regulate by writing, I’d have laughed in your face. Loudly and at length.

Go figure.

All Good Letters Have a P.S., I Think.

Thank you for being here, thank you for following, thank you especially for subscribing. All of this substackery of mine is free and will remain that way, which means that if you have chosen to contribute to its and my upkeep,7 in larger or smaller ways, you are doing something you don’t have to do, which makes your generosity that much more resonant, and I am profoundly grateful. If you’re not yet part of that contributing crew and there’s a part of you that’s thinking “Who would have thought that apostrophes and old movies could be so much fun?” and you choose to join the crew, I will be eternally (or at least monthly or annually) in your debt.

Benjamin

Toward the end, I was headhunted (who even knew that there were restaurant headhunters?) for a managerial spot at the Royalton Hotel off Times Square, as fancy and shmancy a hotel in those days as a hotel can be. After a genial interview, I was offered a five-day-a-week eight-till-four shift. Eight in the evening, I was informed, till four in the morning. And that was when I declared myself officially Too Old For This Nonsense.

It’s Union Square Cafe, by the bye, if that means anything to you.

Or, I dunno, died of drug and drink. Which somehow (I note airily now that it’s way too late for it to happen, tap wood) feels likely.

Two of my regulars were Graydon Carter and Kurt Andersen of Spy magazine, and it amused me no end, years later, as managing editor and copy chief of Random House, to be able to tell Kurt, by then an RH author (and a fine one), that I used to serve him his lunch. (“Did I tip OK?” “Very.”) I also once—I offer this as a reward to you faithful footnote readers—waited on Suzanne Pleshette, and oh my that was fun. (She drank a lot of coffee, as I recall.)

I find few things as pleasant when I’m on my own, especially when I’m traveling, as bellying up to a restaurant bar and taking my meal at the marble counter. First, it saves one from that forlorn Miss Lonelyhearts sensation of occupying a table on one’s own and making conversation with the thin air; second, it seems to amuse the bartenders. Plus the light’s usually better for reading.

I’m not being funny; that’s literally what it’s called.

Aaahhhh...thank you for taking me back (via your footnotes) to the halcyon days of my youth, when I had a subscription to Spy Magazine. One of my favorite recurring bits was Graydon Carter's referring to a certain NYC real estate "tycoon" as a "short-fingered vulgarian." 🥰

Just wonderful story-telling.